Mario Draghi emerged last week from the much-awaited meeting of the ECB Governing Council meeting clutching a fairly bland official communiqué which extended the envisaged freeze on interest rates out to the latter part of next year (aka, ‘forward guidance’), pledged that there would be no shrinkage of the Bank’s securities portfolio (so-called ‘quantitative tightening’) for some considerable period after that ended, and gave details of the terms on which the next batch of loan socialization can be refinanced under the aegis of its TLTRO III programme. [First Published June 7th]

But, sly as ever, Draghi then spent the bulk of the succeeding Q&A session with the press effectively breaching the confidentiality of the meeting and outflanking his opponents by painting an unashamedly one-sided picture of what had gone on in that conclave of monetary cardinals.

Were rates next as likely to rise as to fall, he was asked. No, he roundly replied before craftily cutting the ground out from any dissenting colleagues on the Council by revealing that a number of others has ‘discussed’ reducing rates and also restarting massive asset purchases. Draghi even gave a nod to the primitivism that is ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ by hinting that, next time around – and in complete contradiction of everything any ECB grandee has ever previously had to say on the subject – ‘certainly fiscal policy will have to also come into consideration and play a fundamental role’– i.e., government deficit spending will have to increase, handily assisted by the purchase of the newly-issued debt by the central bank.

In that regard, he then engaged in a back-flip of sophistry by saying that even the Italians did not have to lower their debt burden too rapidly: they just needed to present a ‘credible, medium-term’ plan to address it.

Perhaps the former colleagues whom you oversaw at Goldman Sachs might be able to help out there, as they did so successfully with Greece, Signor Draghi?

Draghi further boxed in his successor by alluding to the tightening effect of a rise in the euro evidenced as the market began to ponder the likelihood of a near-term Fed rate cut (something which also ought to give pause to those who’ve discovered a greater enthusiasm for the single currency this past week).

Finally – in a concluding passage which would make any old school central bank groan with despair – Draghi told his interlocutors that while there seemed to be a certain ‘disconnect’ between what markets were pricing and what surveys reported about future prospects, ‘we have to… take this reading seriously and be prepared.’

The Market Dog will therefore be out frantically chasing the ECB tail and vice versa, just as seems to be happening in the US.

The great question in all this is whether a continuation of negative interest rates is actually what Europe needs in order for its economy to thrive. To address this, a few glib comments about how the Council had largely dismissed ideas that NIRP was detrimental to banks were all that was on offer, despite this being at odds with the verdict of a net 73% of bank responses to the most recent of the ECB’s own regular bank lending surveys.

Worse still, a new working paper has just gone up on the ECB website where four of its in-house Sorcerer’s Apprentices contrive to argue that deeply negative rates can easily be made effective by ‘healthy’ banks through forcing their cash-rich corporate clients to dispose of their nest eggs and ruch to acquire non-monetary assets instead – or rather, increase ‘investments’, as the academics rather naively put it.

Which is great insofar as it goes. But it begs the question of what happens to the poor fools who next get landed with the surplus monies once they are spent. It also avoids dealing with the fact that perhaps corporate boards and their shareholders to whom they are responsible know better how to manage the balance of their property than do a few overly mathematical, PhD scribblers.

Missing, too, is any concept that to provoke what wiser economists might refer to as ‘monetary disequilibrium’ is not a thing to be undertaken lightly. The irony here is that a rush to buy physical goods in order to avoid the pain of having one’s money in one’s pocket dwindle in value is exactly what characterizes the worst and most destructive phase of the very inflationary episodes that central banks are supposedly ‘mandated’ to prevent – the dreaded ‘Flucht in die Sachwerte‘, as Mises termed it – and here we have the pet intellectuals of one of them promoting such a state of economic bedlam as answer to the problems of the moment!

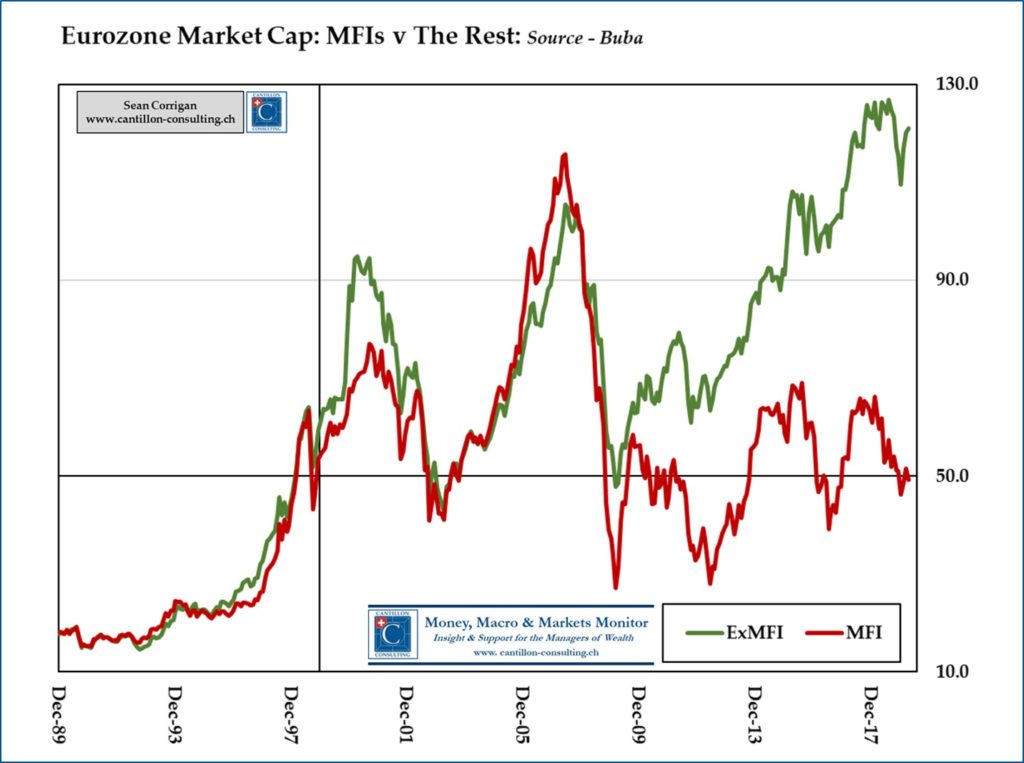

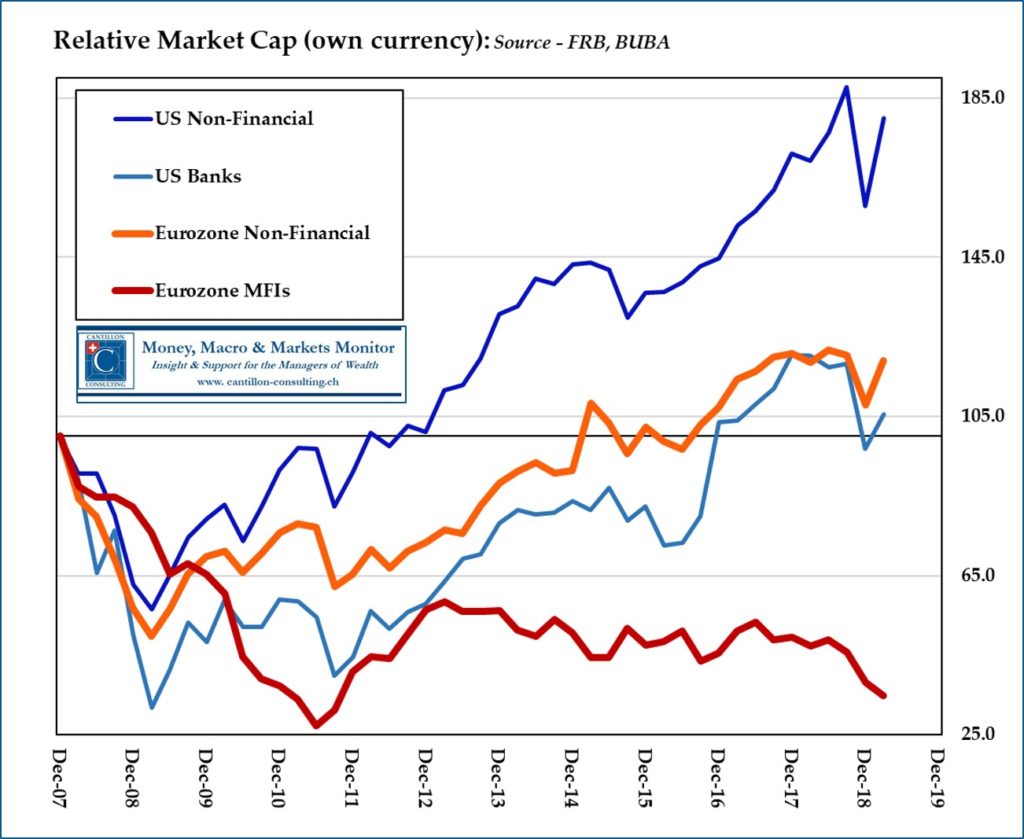

A glance at the disparity between the performance of Eurozone financial corporates – and especially of its banks – and those of both non-financial companies at home and their American counterparts abroad since the late crisis – and more especially since the launch of the ECB’s ‘expanded asset purchase programme’, or APP, in 2015 – should give the lie to the misguided idea that the policy Draghi has unremittingly pursued has been both effective and free of any collateral damage.

Essentially, what the ECB has done in that time is to co-opt the business of credit creation, almost in its entirety, and it has done so largely, though not exclusively, by weakening the stronger pillars of the financial system in order to shore up the weaker, and by favouring the least productive parts of the economy – government and real estate – at the expense of the more vibrant. But then, padre e figlio, the Draghis have long been associated with Italy’s state-capitalist giant, child of the 1930s, the now-defunct IRI.

A few brief figures, comparing the Eurozone’s with America’s experience should highlight the argument.

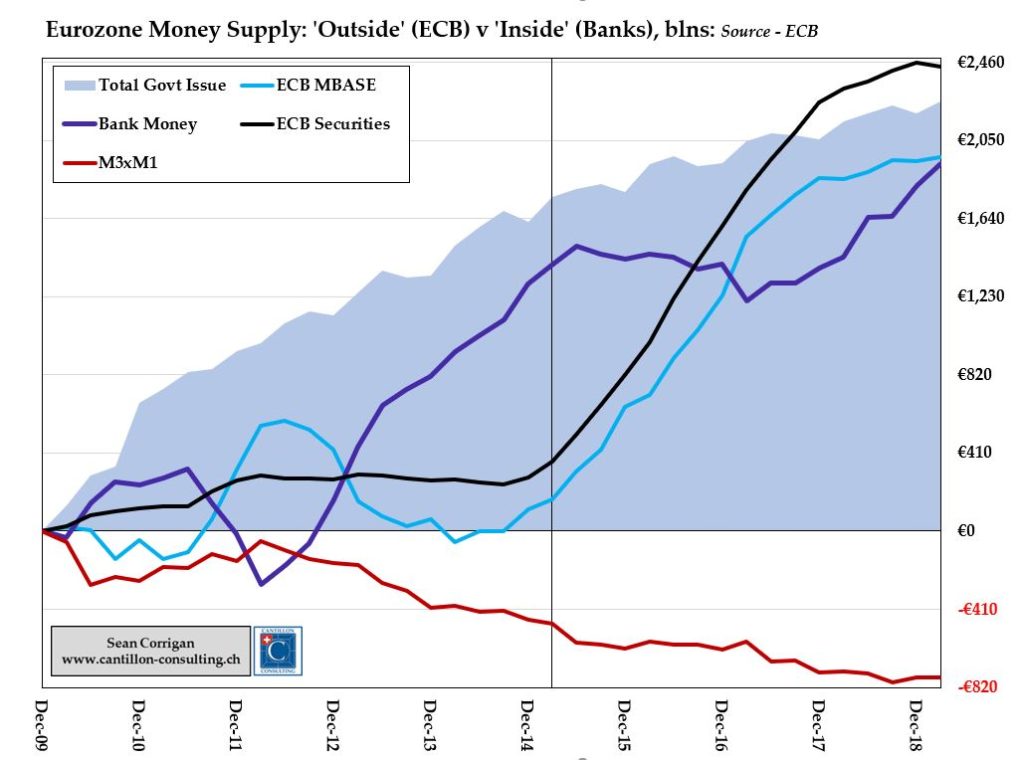

In the four years between 2015’s first quarter and March 2019, by virtue of buying over €2 trillion (sic) of securities – three-quarters of them government bonds – the ECB pumped up the so-called monetary base on which all other forms of money and credit are supposed to be pyramided in ever-increasing quantities by a massive €1.8 trillion, doubling what was already a highly swollen starting total as it did.

And what was the outcome?

Banks added to it less than a third of that sum of their own volition, not the sizeable multiples which classical banking theory suggests they should. Further diluting the impact, they also actually saw their contribution to the ‘higher’ credit aggregates shrink as all the other constituents of the widely-monitored M3 measure fell by almost €300 billion. Effectively, then, the ECB itself contributed almost 90% of all net new banking credit and forced banks to swap earning assets for those whose custody attracts a penalty charge – and it talks of not having ‘run out of space to act’?

Who used the money? Well, in that same stretch, Eurozone governments issued a net new €500 billion in debt (all of it destined at one remove for Signor Draghi’s war-chest), households borrowed a like amount in a Red Queen race to push up housing prices all across Europe and non-financial businesses ended up with a mere €110 billion in extra loans – a paltry sum which works out at around 0.6% a year, compounded, and one which was largely offset by an €85 billion drop in banks’ bond holdings, into the bargain.

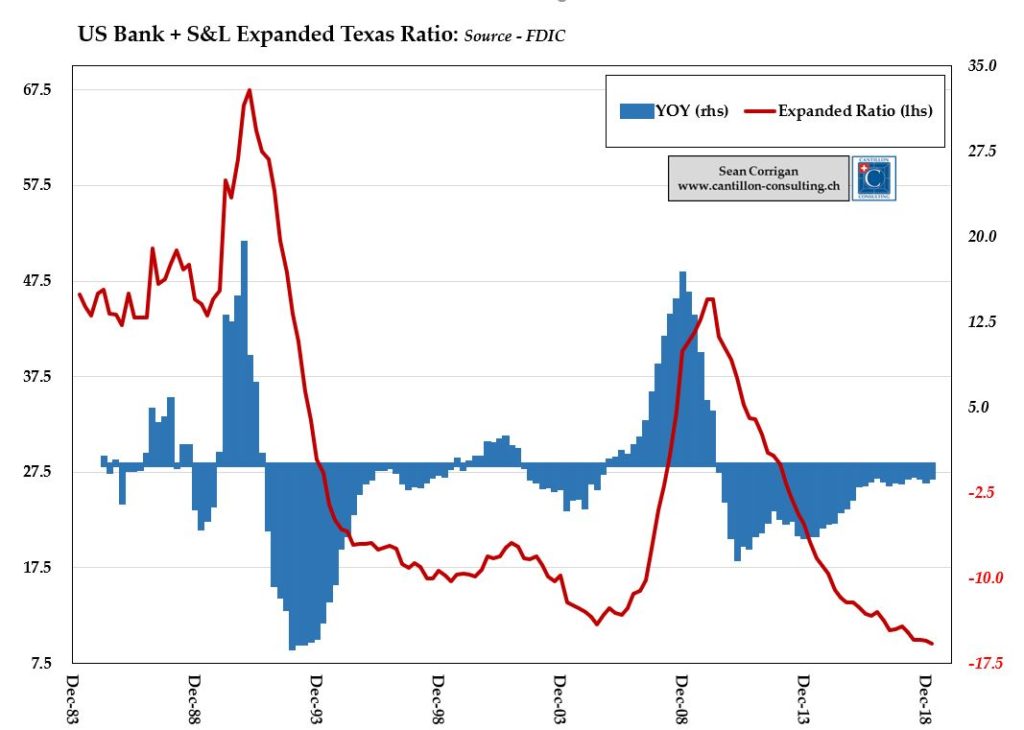

In the US, by contrast – where, remember, banks are much less pivotal in keeping the wheels of industry turning – around €2.4 trillion in new credit was added even though the Fed’s base money fell by €650 billion and its security holdings by €425 billion. US banks – which are, according to the latest report of their regulator, the FDIC, in their best all round condition of at least the past 35 years – simply smiled at the cut in the mountain of largely redundant reserves created by succeeding rounds of QE and, further incentivised by the modest rise in interest rates, got on with doing what it is we expect commercial – not central – banks to do and lent. For comparison, some €465 billion of that was in the form of what the Americans call ‘commercial & industrial’ loans – 4 ½ times what Europe’s banks managed to provide in the loosely equivalent form to their business customers.

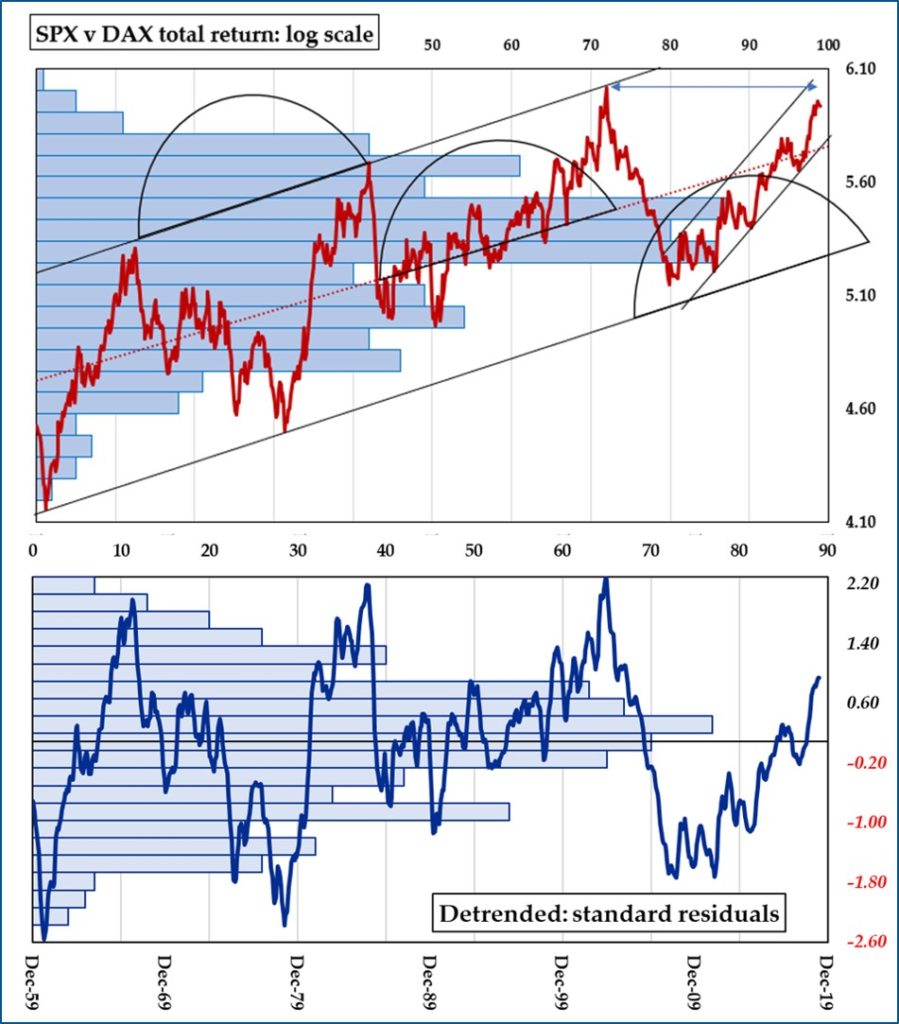

Though now perhaps beginning to stumble, is it any wonder the US economy – and US equity performance has put Europe largely to shame over this same horizon?

But, to suppose that either logic or a simple examination of the facts themselves will deflect the ECB from its chosen course is to move well beyond hope and into the realms of fantasy.

A more realistic prognosis would have the European financial sector stuck in the No Man’s Land of NIRP long into the foreseeable future. Banks will thus have little real role to play, fewer opportunities to make money in any more widely productive manner, and yet none will be allowed to fail. Insurers and pension companies will continue to have to take greater risks with their clients’ monies in a world where even a ramshackle polity like Greece can borrow 10-year funds at less than 3% and, at the same time, will have to operate in a tightening vice of costly regulation. Corporate pensions will face large actuarial deficits and so suck cash flow out of in-house capital investment. A demographically ageing population will struggle to provide for its retirement and so may not be fooled into spending more liberally – as is the central bankers’ express wish – but rather the converse.

The curse of cheap money – Mario Draghi’s principal legacy – is here to stay, it seems.