‘The Future of Finance’ was a conference convened in May 2013 by the Knowledge Transfer Network with the support of, among others, the Institute for New Economic Thinking and Oxford’s Said Business School. As part of the programme, a debate was staged between the representatives of four ‘schools’ of economic thought – the Monetarists, as represented by the former ‘Wise Man’ Professor Tim Congdon; the Keynesians, as championed by Christopher Allsopp, formerly of the BoE’s MPC; the Complex Adaptive Systems approach of Professor Doyne Farmer of ‘Newtonian Casino’ fame, and the Austrians whose corner was fought by yours truly.

The following essay attempts to expand upon the arguments I made that night in what was obviously a much more concise form, together with some more general thoughts thrown up by the conference at large. Since the event in question was deliberately – if courteously – adversarial and given that it was consciously staged as a species of entertainment, rather than one of deep academic debate, it will be apparent that none of us protagonists were fully able to develop our views beyond what could be incorporated into a few minutes’ pitch to our audience.

Moreover, none of us were allowed any subsequent opportunity for further attack or rebuttal, but could only respond, in the round, to a sampling of questions posed by the audience. In the circumstances, if the arguments of my opponents seem in anyway superficial as I summarize them here, I trust they will be gracious enough to accept, by way of an apology, the acknowledgement that my own propositions on the night will have seemed no less denuded of context or justification than perhaps did theirs.

Their bloody sign of battle is hung out

Ladies and Gentlemen, if you have heard of us ‘Austerians’ at all, you probably have in mind a caricature of us as loony liquidationists, eager for a Bonfire of the Vanities in which to purge the sins of all those who seem to have enjoyed the late Boom rather more than we did as we paced up and down outside the party, weighed down with our sandwich boards on which were emblazoned the injunction, “Repent Ye now for the End is nigh!”

Naturally, I don’t quite see it like that, nor do I feel shy about proclaiming our virtues over those supposedly possessed by the Tweedledee and Tweedledum of macromancy – the monetarists and the Keynesians – whose alternating and often overlapping policy prescriptions have, in the immortal words of Oliver Hardy, gotten us into one nice mess after another.

The monetarists – or perhaps we should call them the ‘creditists’, since they are not often overly clear about the crucial distinctions which exist between money, the medium of exchange, and credit, a record of deferred contractual obligation – tend to be children of empiricism. I hasten to add that, for an Austrian, there are few greater insults that can be bandied about: Mises himself once waspishly observed that the modern dean of monetarism, Milton Friedman, was not an economist at all, but merely a statistician.

To digress a moment, ‘money’ is different from ‘credit’ and the refusal to consider how, or in what manner is what leads to many errors, not just of thought but also of deed, for if there is one thing that modern finance is pre-eminently equipped to do, it is to transform the second into the first and thereby pervert the subtle webs of economic signalling which are so fundamental to our highly dissociated yet profoundly inter-dependent way of life.

We could of course come over all philosophical about money being a ‘present good’ – indeed, the archetypical present good – and about credit being a postponed claim to such a good. We could then go on to point out that, far from being a scholastic quibble, such a distinction is of great import to the smooth functioning of that vast assembly line which we call the ‘structure of production’ and that to subvert their separation is to call up from the vasty deep the never-quite exorcised demons of the ‘real bills’ fallacy and to begin to set in train the juggernaut of malinvestment which will soon induce a widespread incompatibility among the individually-conceived, yet functionally holistic schemes of which we are severally part and so lead us through the specious triumph of the Boom and into that grim realm of wailing and the gnashing of teeth we know as the Bust.

Later, we shall have more detail to add to this, our Austrian diagnosis of the role of monetized credit in the cycle, but for now let us instead point out that money is a universal means of settlement of debts and thus acts as a much-needed extinguisher of credit. In making this assertion, I have no wish to deny that the latter cannot be novated, put through some kind of clearing mechanism, and hence cross-cancelled, in the absence of money – as was the often nearly attained ideal aim at the great mediaeval fairs, for example – simply that the presence of a readily accepted medium of exchange greatly facilitates this reckoning. Furthermore, though a new crop of expositors has sprung up to make claims that credit is historically antecedent to money (though the plausible use of polished, stone axe-heads as a proto-money which was current all along the extensive Neolithic trade routes of 5,000 years ago might give us renewed cause to doubt this now-fashionable denial), this is hardly to the point in the present discussion.

Money may or may not have sprung up, as is traditionally suggested, to avoid the well-known problems of barter, but, however it arose, what it did do was obviate the even more glaring impediments of credit – namely that, as the etymology of the word reminds us, ‘credit’ requires the establishment of a bond of trust between lender and borrower, a trust whose validation is, moreover, subject to the vicissitudes of an ever-changing world by being a temporally protracted arrangement.

Thus, while money’s joint qualities of instantaneity and finality may confer decided advantages upon its users, its main virtue indisputably lies in the impersonal nature of its acceptance in trade for it is this which frees us from the limited confines of our networks of trust and kinship and so greatly magnifies the division of labour and deepens the market beyond all individual comprehension in a mutually beneficial, ‘I, Pencil’ fashion.

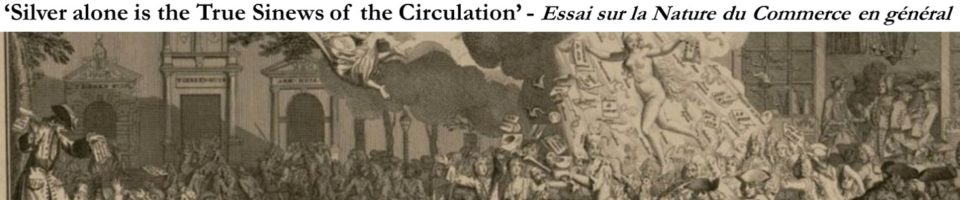

For its part, credit certainly may help us get by with less money, never moreso than when we have become drunk on its profusion and giddy at the possibilities this abundance seems to offer amid the boom. Then, we may truck and barter more and more by swapping one claim for another almost to the exclusion of the involvement of money proper but, as the great Richard Cantillon pointed out almost three centuries before Lehman’s sudden demise forcefully impressed the lesson upon us modern sophisticates once more, ‘…the paper and credit of public and private Banks may cause surprising results in everything which does not concern ordinary expenditure… but that in the regular course of the circulation the help of Banks and credit of this kind is much smaller and less solid than is generally supposed.’

‘ Silver alone is the true sinews of circulation.’

Scylla & Charybdis

But back to our main theme. The devotees of monetarism start from the observation that what they call ‘money’ tends to move in a loose correspondence with a statistical chimera called ‘National Income’ and then proceed to reverse the usual order of the harnessing of cart to horse to suggest that this income is best controlled by manipulating the quantity of ‘money’ ex ante (and here let us spare ourselves an examination of the exact definition of that beast, in keeping with the monetarists’ own proclivity to flit promiscuously between whichever of the likes of M1, M2, M3… M(n) currently best fits the econometric bill).

Leaving aside the vexed question of what exactly comprises ‘national income’ or of whether the near infinite richness of the interactions taking place between tens – if not hundreds – of millions of people can be boiled down into one simple numerical entity, it is not really surprising that, in a horizontally-diverse, vertically-separated, modern economy, the multifarious business of accumulating, transforming, and delivering a wide array of goods and services involves the generation of a commensurate number of claims so that each individual’s part in the creation of this bounty can be duly recorded and ultimately encashed.

But it is a long way from recognising that a degree of correlation might exist between money and credit on the one hand and material wealth on the other to insisting that the forcing of extra claims upon the system can somehow encourage an increase in genuine business, an augmentation of prosperity, or a sustainable improvement in the common weal.

To believe that wonders can be enacted merely by tinkering with the availability of the medium of exchange which is our economic system’s basic plumbing is a bit like the brewer who thinks that his beer can be made to ferment quicker and taste better if only he can lengthen the span and widen the bore of his pipe-work, or like a would-be author who thinks his magnum opus is more likely to be recognised as a literary masterpiece if he doubles the spacing between the lines of his typescript and so uses twice the number of reams of paper to set it down.

This is not to say that we Austrians deny that such jiggery-pokery can have very real effects on the economy – we are, after all, the ones who are noted for our own, unique, Monetary Theory of the Business Cycle – but we do doubt that its effects are either so mechanically predictable or so universally benign as do our esteemed Chicagoan colleagues.

Furthermore, we are all too aware that the monotonic and comprehensive inflation of values which results from the kind of carpet-bombing, ‘helicopter drops’ which loom so large in the dark fantasises of our central banking chiefs are not the norm, but that money creation takes place at specific times and specific places and so raises some prices and enhances some demands before it effects others, thus causing all manner of largely incalculable disruptions to the all-important relative price relations which are the means by which we can determine how scarce one good is compared to another. Thus, each of their successive interventions is only likely to introduce further strains into what the earlier ones have made an already highly dislocated structure to the point that the malign effect of such distortions seems to require yet further acts of interference with the natural order.

As for the Keynesians – one almost fails to know where to begin with a hodge-podge of obscurantism which is at best a rehashed version of the old under-consumptionist fallacies, shot through with a dash of equally antediluvian mercantilism, and at worst a cynical excuse for central planning and an assault upon the sphere of private decision making.

Not the least of the sins of dear Maynard was his role as a ‘terrible simplificateur’ in his championing of a school of accounting tautology that too many of us have come to revere as ‘macroeconomics’ – a many-headed monster of a thing which all too often tends to controvert the eminently sound insights of micro-economics once the latter’s transaction count crosses some strange, reverse quantum threshold of weirdness.

We have heard some of the peculiar effects of this tendency here tonight in being assured, among other things, that the only salvation of a people brought low by borrowing too recklessly is to find another agency – Burckhardt’s arch ‘swindler-in-chief’, the state, if no one else – to take their place at the high table of prodigality.

We have also been told that public debt is an ‘asset’ that we owe to ourselves – a contention which not only flies in the face of logic, but also of much of history – and that we cannot all export our way out of difficulty, when the very marvels of modern society have been exactly so built up by each man, much less each nation, ‘exporting’ as much value as he can to his fellows, thereby earning the right to ‘import’ as much as he would like from them as his due reward.

Above all, we have been enjoined to assume that everything wrong in the outmoded world of laissez-faire is the consequence of someone – usually someone assumed to reprehensibly better-off than the norm – failing either to exhaust the entirety of his income on fripperies – so triggering a nonsensical ‘paradox of thrift’ – or to spend any such surplus of income over outgo on fixed income securities – so delivering us to the legendary Château d’If of the ‘liquidity trap’ instead.

Needless to say, we hold the opposite to be true. We hold that thrift fuels, rather than frustrates, material progress and that the only ‘liquidity trap’ we have to fear is the snare that results from the provision of too excessive a supply of ‘liquidity’ – i.e., of a great superfluity of money and the promise of artificially cheap credit for ‘as long as it takes’ – in the aftermath of the Bust. This utterly wrong-headed approach only attenuates the purgative effect of the crash and so leaves too many men, machines, and minerals locked into too many failed endeavours at what are still too-elevated prices for their redeployment to alternative uses to promise a decent return on the undertaking, this preventing economic rejuvenation.

In the authorities’ Humpty Dumpty compulsion to validate every sunk cost by suppressing interest rates – and thereby suppressing a good deal of the useful risk appetite and channelling too much of it into the narrow field of financial speculation – they only succeed in sapping the survivors of their remaining vitality. On the one hand denying the least afflicted (among whom are to be found, by definition, our potential saviours, the wiser, the more resilient, and the more flexible) the opportunity to rebuild amid the rubble, they thereby hand the reins instead over to an enervating alliance of extractive, public-choice parasites, skulking subsidy-grubbers, feckless leverage jockeys, and special-pleading, sub-marginal zombie companies.

Among other enormities, the fact that production must necessarily precede consumption and that it is the first which comprises the creation of wealth and the second which encompasses its destruction, was far beyond the ken of the spoiled Bloomsbury elitist who exhibited a life-long contempt of the aspirations and mores of the bourgeoisie and who hence imagined that policy was at its finest when, like an over-indulgent aunt, it was pliantly accommodating the otherwise ‘ineffective’ demand being volubly expressed by the old dame’s petulant nephew as he stamped his foot in the tantrum he was throwing up against the sweet-shop window.

Been there, done that, bought the T-shirt

The guilty secret shared by many disciples of these two schools is that they are well aware that theirs is very much a busted flush, as is made plain by the procession of very public breast-beatings and existential re-examinations which they have conducted in the years of post-Lehman purgatory by way of atonement for their failures. Indeed, one measure of the dissatisfaction felt at the failings of these Terrible Twins – the money illusionists and the flushing-toilet hydraulicists – lies in the attention now being focused on the work being done by my third opponent and his peers under the guise of the ‘complex adaptive system’ approach.

To an Austrian, in truth, there is much about this last that seems thoroughly unobjectionable, so much so that it is hard to resist an invocation of Gunnar Myrdal’s trenchant dismissal of Keynes’ for his linguistically-challenged commission of the sin of many a monoglottal, English-speaking economist – that of ‘unnecessary originality’.

I say this because in many ways the Complexity guys are simply putting a computer-age spin on concepts we have been trying to articulate for the past three generations.

We, too, start from the bottom-up by focusing on the individual – or the ‘agent’ as he is now known. We, too, believe that order is emergent, knowledge is dispersed, network effects are key, and that the attainment of equilibrium is a mirage.

Where I suspect we differ is that we are more radically subjectivist in a way that it cannot be possible to capture in a mathematized ‘model’. One might also be dubious about the degree of ‘scientism’ involved – i.e., the extent to which there has been an invalid application of the precepts of physics to what is after all a social phenomenon. One might also be wary of the inherent dangers of being too prescriptive in laying out what the ‘agents’ may or may not do.

Among the caveats is the fact that we Austrians hold that scales of preference and utility are ordinal, not cardinal, and so are not arithmetically tractable. Moreover, we cannot see it as a complete solution to go to the trouble of atomizing what was formerly a faceless, monolithic ‘aggregate’ only to have to deny the atoms their own individuality, however capricious their expression of this property may be. We must be wary therefore of driving out the ghost and leaving only the machinery behind.

Nor do we then want to thrust our poor little cellular automata into a Game of Life whose inevitably arbitrary choice of rules is predicated on the very same contradictory framework from which we are trying to free ourselves – namely, the one prescribed by the traditional schools of macromancy. Not only would we wish to avoid our agents’ freedoms being prejudiced by the suppositions of the mainstream, we would also wish them to do more than play out a mere financial simulation, however rich it might be in revealing the structural flaws in our existing institutional architecture and in warning us of its proclivity to the negative feedbacks, price cascades, and other malign outcomes which have come to plague it.

For us, a better imagined microcosm would include scope for the real-world action of entrepreneurs, those principal vectors of eco-genetic adaptation and selection, those drivers of change and arbitrageurs of profitable possibilities, the men and women who are constantly seeking out new combinations of action and innovative mixes of things in order to deliver more value at lower cost to a wider range of customers. Any toy universe which leaves out a reasonable representation of entrepreneurial endeavour – and the fact that this quintessential force for betterment thrives best in conditions which lie outside the bounds of equilibrium, yet away from the ragged edge of chaos – is likely to produce a poor facsimile of the real economy.

Our stipulation for an improved virtual landscape would also insist it addresses a major failing of mainstream macro, viz., its poor handling, if not outright neglect, of the role of capital – a critical construct which is neither a financial variable (despite the unfortunate overlap of terminology with the world of book-keeping) nor, strictly, a mere physical entity like a factory or a machine tool, but which is rather a hybrid which includes both the use of the Thing and the process by which it is employed such that ‘capital’ becomes as much a verb as a noun, if you will.

It may be that we do a disservice both to the judgement and the ingenuity of our Complex System friends, but it does seem questionable that the kind of ‘experts’ they are likely to have consulted would have advised them to incorporate such features when writing their programs just as it is beyond our ken as to exactly how they would go about doing so, even if asked.

If it really is the case that either they have not or they cannot, theirs must very much still be considered a work-in-progress and not yet a fully-formed tool of analysis.

Et in Arcadia ego

Having broadly tried to demonstrate where we differ from our rivals and where we find their tenets most objectionable, you might be hoping that I will now be tempted to go into the details of what an Austrian might recommend by way of a remedy for our current ills even though this would exhibit a clear infraction of Hayek’s admonition that ‘the curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design’!

So, rather than having me succumb to such a ‘fatal conceit’, let me instead sketch the outlines of what would, in an Austrian estimation, be a world in which we would be unlikely to repeat our present stupidities, certainly not on the Olympian scale on which we currently practise them.

Firstly, we should recognise that much of our success as a species comes from our adherence to that peculiar form of competitive co-operation which we Austrians term ‘catallactics’ – i.e., the business of exchange, of trading the fruits of our varying endowments, aptitudes, and accomplishments to the mutual benefit of both counterparties to what may well be a single-priced transaction but which is nonetheless never a zero-sum one (at least when it is undertaken voluntarily and in good faith).

As a direct consequence of this, we can assert in the strongest possible terms that we therefore tamper with the means by which we conduct such dealings – we meddle with our medium of exchange, our money – only at our peril. To us, dishonest money is the root of all evil, not ‘shadow banks’, ‘moral hazard’, ‘regulatory capture’ or any of the manifold offshoots of human cupidity in general, for the ability of such perennial failings to wreak widespread havoc in either financial markets or economies, per se, would be much more severely limited if money were not so easily corrupted alongside the men who use it.

A good deal of discussion has taken place at this gathering and many ideas have been thrown up – many of them earnest, most of them shrewd, some of them even practicable – as to how to improve our present modus operandi. But unless banking and finance better reflect economic reality – and by this I mean of course Austrian reality! – all of them will be in vain: not so much shuffling the deckchairs on the Titanic as pruning the vines growing on the slopes of Mt Vesuvius, perhaps.

It should be further recognised that a vital subset of our economic interactions consists of that swap of jam today for jam, not just tomorrow, but for a long succession of tomorrows that we might more grandly term ‘intertemporal’ exchange. Indeed, it can be argued that this process is even more intrinsic to our humanity: that the move away from such hand-to-mouth activities as scavenging, foraging, and predation and towards the rational provision for the future by means of forward planning is very much what put the sapiens into the Homo, way back when Also sprach Zarathustra was first ringing out as the soundtrack to Mankind’s great Odyssey from the campfire to the Computer Age.

It is in this devotion of forethought and its associated deferral of immediate gratification where the concept of ‘capital’ first comes into our story and while this opens up before us a vista of riches bounded only by the interplay of our imagination and our willingness to make a short-term sacrifice in order to gain a longer term advantage, it is intrinsically fraught not only with estimable risk, but with unknowable uncertainty, as well as being subject to the further proviso that our own actions’ influence may well serve to increase the range of possible outcomes far beyond what we had first thought likely.

Keynes himself waxed lyrical about the ‘dark forces of time and ignorance’ – even if his own teachings have done more than most over the intervening years to enhance the occultation and obscurity against which his fellow men would have to contend – so it should not come as a surprise when we next insist that none of our man-made institutions can be said to be well-crafted if they aggravate these difficulties.

Economic institutions should thus allow information to percolate in as uncorrupted a manner as possible and should allow for feedback signals to be generated in as direct and unequivocal a fashion as they can. These should clearly flag where both success and failure has occurred so that useful adaptations can proliferate while the ineffective ones are abandoned as rapidly as can be. In essence this means that we much not pervert prices and, since every price is necessarily a money price, the unavoidable inference is that we should not mess with money.

A corollary to this is that there should be the least possible impediment to any and all such adaptations being attempted; indeed, much Austrian ink was spilled during that dark decade of the 1930s in arguing that the surest remedy for the many ills then afflicting the West was to sweep away the obstacles to change and to lubricate the working of the machinery – to practice a policy of Auflockerung, in the phrase of the day.

Following on from this, it should be evident that property should be inviolate and the wider rules of contract should be both transparent and consistent in their application. The law should be concerned principally with equity, the courts with providing a cost-effective and disinterested forum for the arbitration disputes arising from any violations of the first and of any failure to fulfil commitments freely made under the second. Aside from the many ethical considerations attaching to such a demand, we would argue for it additionally in terms of the need to reduce all the uncertainties under which men must act to their achievable minimum if we are to encourage the widest degree of peaceful association, the richest web of commercial relations, and the greatest degree of capital formation that we can.

What we do not want is to be inflicted with a shifting snowball of often retro-active regulation. We must avoid a diffusion or supersession of individual responsibility and desist from fuzzy, catch-all law-making – in fact, we should tolerate as little legal positivism as possible, especially of the kind enacted, often cynically, during periods of crisis. We must insist that the state offers neither explicit nor implicit guarantees, that no bail-outs, or back-door favours be extended to the privileged few at the expense of the disenfranchised many. Finally, it should be impressed upon our elective rulers that the politics of disallowing loss, however well-intentioned, is nothing more than a policy of disavowing gain.

Though there are wider ramifications, the worlds of money and finance should, of course, be subject to all the above strictures. Here, we would again emphasize that to interfere wilfully with the substance of our money is to put oneself in breach of most of these guidelines; indeed, that this is perhaps the most heinous of all infractions, since it entails the most pervasive attack upon both property and the sanctity of contract that there can be since it involves a post hoc and highly arbitrary change in the dimensions of the very yardstick by which the terms of all such agreements are drawn up.

We would further contend that the paving stones on our road to the future, on the intertemporal highway whose praises we have already sung, are nothing more than our investments. These should be funded with scarce savings, not financed by the paltry fiction of banking book entries and hence the business of investment should be conducted only in accordance with the balance we can jointly negotiate between our current ends and our ends to come; that is, on a schedule which naturally emerges to reflect our societal degree of time preference and which does not emanate solely from the esoteric lucubrations of some central banking Oz.

Progress may less spectacular this way, unpunctuated as it will be by the violent outbreaks of first mass delusion and later disillusion which comprise the alternations of Boom and Bust. But it will be, by that same measure, steadier and more self-sustaining. Absent such a condition, the fear I have already raised is that all the well-meaning calls for better financial regulation and more condign penalties for banking malfeasance are so many straws in the wind as far as a better functioning financial apparatus is concerned.

In passing, the very fact that we are all gathered here to bring so much effort and expertise to bear on the problems thrown up by our contemporary methods of finance shows just how far we have strayed from a true appreciation of its abiding scope as what is effectively little more than a glorified, if somewhat disembodied, form of logistics. Finance should be a record of the assignment of goods and property rights across time and space – a four-dimensional bill of lading, as it were. It would be better were it seen for what it is – a means and not an end; the flickering reflection of a deeper Reality on the wall of Plato’s cave, not a towering 3D IMAX rendition of a screenwriter’s imagining. It should once again be valued only as the carthorse and not as the cargo he pulls behind him.

Time and Money

Here we come full circle, for what this essentially presumes is that there exists no mean by which to achieve the ready monetization of credit since that insidious process – which is one favoured equally by the fractional free bankers as much as by the central banking school and the chartalists – breaks the critical linkage of sacrifice today for satisfaction tomorrow which is what ensures that we do not overstretch our resources or overextend the timelines pertaining to their employment.

Though we have already touched upon the basis for this affirmation, it is so pivotal to the argument, that I will test your indulgence in trying to bring home the point, once and for all.

When credit is not erroneously transmuted into money, it means that I, the lender, cede temporary control over my property to you, the borrower, postponing my enjoyment of the satisfactions it confers because you have made it plain to me that your desire for it is currently greater than mine. This difference in preference is – like all such disparities – an exploitable opportunity for us both and, recognising this, my existing claim over a specified quantum of current goods is voluntarily transferred to you, meaning I must abstain from its consumption (whether productive or exhaustive) while you partake of it in my place in what is a wholly co-operative and, moreover, a logically and physically coherent exchange.

You, in return, promise to render me a somewhat larger service some specified time hence, as the reward for my forbearance and the price of your exigency. That surplus – what we regard as the interest payable – will therefore be seen to be the price of time not of money, much less of ‘liquidity’ as the Keynesians would have us believe. Hence, it emerges as a phenomenon much more fundamental to our psychology as mortals and to the Out of Eden impatience with which this afflicts us than to any happenstance of the ‘market for loanable funds’. Once you accept this interpretation, you are at once made aware of just what an abomination is an officially-sanctioned zero – or in some cases, a negative – interest rate and you are presumably one step from wondering whether this monstrosity can be anything other than unrelievedly counter-productive.

Next, however, imagine that I take your IOU to the bank and that peculiar institution registers my claim upon its (largely intangible) resources in the form of a demand liability of the kind which – by custom, if not by legal privilege – routinely passes in the marketplace as money. Your promissory note – a title to a batch of future goods not yet in being – has now undergone what we might facetiously call an ‘extreme maturity transformation’ which it has conferred upon me the ability to bid for any other batch of present goods of like value without further delay. It should, however, be obvious that no such goods exist since you have not had time to generate any replacements for the ones whose use I, their lender, supposedly forswore until such time as your substitutes are ready to used to fulfil your obligations, something we agreed would be the case only at some nominated point in the future.

More claims to present goods than goods themselves now exist (strictly speaking, the proportion of the first relative to the second has been artificially increased) and thus the actions we may now simultaneously undertake have become dangerously incongruous. Our initially co-ordinated and therefore unexceptionable plans have become instead a cause of what is an inflationary conflict no less than would be the case if I had sold you my place at the head of the queue for the cinema only to try to barge straight past you in a scramble for the seat in question.

What is worse, is that this disharmony will not be limited to us two consenting adults – indeed, we may both actually derive an undiminished benefit from it – but by dint of the very fact that the disturbance we have caused will ripple through the monetary aether to inflict its pain upon some wholly innocent third party who is blithely unaware of the shift in the monetary relation which we have occasioned with the aid of the bank. In our cinema analogy, the bank has given me a duplicate ticket which will allow me to bump some uncomprehending late-arrival out of the place fro which he has paid and denying him his right to see the show.

Monetization in this manner has done nothing less than scramble the economic signals regarding the availability of goods in time and space. Thus it confounds rational economic calculation in the round and so begins to render honest entrepreneurial ambition moot. Such a legalised misdemeanour is bad enough in isolation, but we know that this will be anything but an isolated infraction. When banks can monetize debts, they will: when they can grant credit in the absence of prior acts of saving, they will – indeed, we demand that they do no less out of the misplaced fear that otherwise economic expansion will be derailed.

The truth is, of course, that the greater the number of economic decisions which come to be conducted on such a falsified basis, the higher and more unstable is the house of cards we are constructing on the credulity of the masses, the conjuring tricks of their bankers, and the connivance of the authorities who are charged with their supervision. Worse yet, the feedbacks at work are such that each new card we add to the pile appears to justify the installation of every other card beneath it and the more imposing the edifice grows, the more eagerly we rush to make our own contribution to this financial Tower of Babel and the more frenetically the banking system works to assist us until it finally collapses under the weight of its own contradictions.

To modern ears, more attuned to the rarefied talk of the exotica of credit default swaps, payment-in-kind junk bonds, and barrier options, this may all seem rather laboured and old-fashioned with its parallels to the classical treatment of the ‘wage fund’ and its echoes of the hard money Currency School which fought the great controversy of the 19th Century with its loose credit, Banking School challengers.

For this I make no apology, for much of what we Austrians stand for can trace its roots back to the reasoning first laid out by Overstone, McCulloch, and Torrens in that grand debate, just as our opponents tonight can trace their lineage back to the likes of Tooke, Fullarton, and Gilbart (I might here blushingly recommend to you a modest little tome entitled ‘Santayana’s Curse’ in which I deal with the relevance of the background to that debate to modern-day finance).

It is also important to bear in mind that the game of finance cannot be conducted in a vacuum, to always be clear that its workings exert a profound effect on everyday decision making and that finance is a force for good when the rules of that game are in harmony with those laws of scarcity and opportunity which govern what is loosely termed the ‘real’ economy of men and materials.

Moreover, the elision of these two types of claims – money and credit – by what must be a fractional reserve bank has dramatically raised the stakes. The near limitless, fast-breeder proliferation of credit which this enables and the facile transformation of this credit into money break all sorts of self-regulating, negative feedback mechanisms between supply, demand, price, and discount rate. Greater, credit-fuelled demand leads to higher prices.

Higher prices should discourage further demand, but instead encourage more people to borrow in order to play for a further rise in prices, just as it flatters the banking decision to grant such loans since the earlier ones now appear to be over-collateralized and their risk consequently diminished. Divorced from a grounding in the world of Things and no longer intermediators of scarce savings but simply keystroke creators of newly negotiable claims, our modern machinery is all too prone to unleash a spiral of destabilizing – and ultimately disastrous – speculation in place of what should be a mean-reverting arbitrage which effortlessly and naturally reduces rather than exacerbates untoward economic variation.

Sadly, my monetarist and Keynesian rivals see nothing but positives in this arrangement and given their unanimity on the issue, I would hazard a guess that the complex adaptive system types are happy enough to bow to this consensus and to accept that this is simply the way things are when they construct their models and run their simulations. The laymen – even the expert laymen, if I may be allowed such an oxymoron – have been even more united in bemoaning anything which might inhibit banks’ ability to shower credit upon everyone and anyone who asks them for it. If we had no shadow banks, who would give the aspiring taxi-driver the price of his medallion or the wannabe nest-maker her mortgage, one participant asked, as if we all took it for granted that to enjoy goods for which one has not earned the means to pay was their god-given right.

Nor do the free-fractional types, as eloquently represented here by Professor George Selgin, have any objection to the mechanism itself, being, on the contrary keen to suggest it will do far more good than harm by dampening down fluctuations which they fear may emanate from a suddenly increased to desire to hold money for its own sake. All they ask is that the ‘free’ banks they advocate are forced to come out from under the aegis of a central bank of issue and away from the current fiction of government deposit insurance and so have no-one to shield them from the consequences of any excess or imprudence into which they might stray.

It will probably not now surprise you to learn that while we agree that banks should indeed stand on their own two feet like those involved in any other branch of business, very few of us Austrians share his sanguinity on this issue, either on theoretical grounds or as a result of our own somewhat different interpretation of the (mainly Scottish) historical record.

For our part, we would rather that the kernel of money-proper around which all other obligations are arrayed is both unable to be near-costlessly expanded at political or commercial will or shrunk as a consequence of any wider calamity. Given this fixity, we trust that any change in economic circumstances will see prices adjust to reflect that without occasioning any major harm (our model economy has undergone a radical Auflockerung by now to ensure this). Nor do we believe that credit will be denied all flexibility, certainly not within the dictates of what the saver can be persuaded to accord to the investor, or the vendor to the buyer.

It is true that this would be a world characterized by the slow decline of most prices as human ingenuity and honest entrepreneurship were continuously brought to bear on the eternal problem of scarcity, but neither would this hold for us any terrors. After the initial transition, people would soon become acclimatized to such a benign environment and would adjust their expectations and their capital structures to best fit it.

As for Professor Selgin’s bogeyman of a sudden tumultuous rush to hold money for its own sake – which apocalypse he fears above all should we prohibit his Free Banks from printing up such liabilities, willy-nilly – we see little reason to believe such impulses could reach very far up the pecuniary Richter scale in a society which had wisely denied itself the volatile mix of massive fictitious capital, extreme leverage, inflationary gambling, morally-hazardous speculation, soft-budget public choice profligacy, and reckless maturity mismatches with which we are so afflicted in our present era of easy-money, chronic price-appreciation, and the granting of overarching central-bank ‘put-options’.

Sound money is more likely to prove conducive to sound business practice and hence to a sound night’s sleep for all.

Credo

To sum up then, the only valid economics is micro, not macro; individual, not aggregate. Value is subjective not objective. The consumer is sovereign in the choice of where he spends his dollar – and all values can be imputed from where he does so – but he should first earn that dollar through his prior contribution to production.

Entrepreneurial discovery is the evolutionary mainspring which drives our secular material advance and the entrepreneurial profit motive – in an honest-money, rent-free world – is the ‘selfish gene’ of that ascent. That same motivation mobilizes the set-aside of thrift in the form of capital and capital – to risk pushing the biological metaphor beyond the point of useful illustration – is the enzyme pathway leading to the synthesis of what it is we most urgently want at the lowest possible cost.

In all of this, the workings of a sound money should be so seamless and subliminal that we pay it no more attention than we do the fibre-optic networks or 4G radio waves used for the transmission of our digital data. Finance should be based on funding – i.e., the sequencing and surrender of the right to employ real resources through time.

That economics is an Austrian economics, not a monetarist one, a Keynesian one, nor a complex-adaptive system one and I heartily recommend it to your consideration.

Sean Corrigan