With many commodity prices touching multi-year lows and with mounting fears for real estate valuations and car-lease residuals, numerous commentators seem convinced that ours is now a deflationary future. QE failed to raise CPI by anywhere near what the spin promised, they say, partly because it was ‘unsupported’ by fiscal policy. Therefore, if we don’t get Roosevelt, we’ll get Brüning, they conclude, and, meanwhile, we need the Fed to cut rates below zero, said one prominent pundit on April 5th. We replied:-

It is not valid to argue that prices will generally fall this time because CPI did not roar higher the last.

This is because (a) the injections functioned differently after 2008 as that was primarily a financial seizure, not a real one, as is today’s; (b) the real assets which fell most in price during the crisis (primarily RE) are the very ones which have since most risen in price (“inflated”); (c) the international division of labour was then undamaged, whereas today it is in serious jeopardy, thanks to China’s (deserved?) vilification.

Incidentally, it is somewhat risible to say there was no fiscal response last time, even if this one is shaping up to dwarf it. Such views are mainly propounded by Keynesian dinosaurs trying to say only their Master’s nostrums can ever be relied upon to work.

Certainly, there are sectors which will fall in price – appreciably so in some cases. We only have to look at the havoc being wrought upon the global energy industry to see this.

But lower prices are not of themselves evidence of deflation: just of a shift in the objects of our spending. As long as the falls do not trigger a disproportionate decline in financial capacity, the losers’ shortfall of revenue can result in a windfall for the sectors on which we do wish to spend our greater residuum of money instead.

To the extent that the labour and capital formerly devoted to the less favoured sectors is free to refashion itself and move into the business of supplying the second, no lasting harm may accrue once the necessary adaptation takes place – which is not to say that this is an evolution whose inherent difficulties we should trivialize,.

Again, the fear must now be that the associated distress heightens calls for further state intervention – a cry that will patently be very welcome to those in office who always long for a greater quantity of Other People’s Money to spend.

It is here that the inflationary influences will be most readily felt. The state, after all, runs only the softest of soft budgets while it is the most wasteful, least productive, most monolithic, and least innovative of spenders. Backed up by a compliant central bank, the phrase ‘monetary ‘authority’ will become even more of a sick joke than it already is.

All of this implies a great deal of (greatly misdirected) demand for not much extra useful – and certainly little profitable – supply.

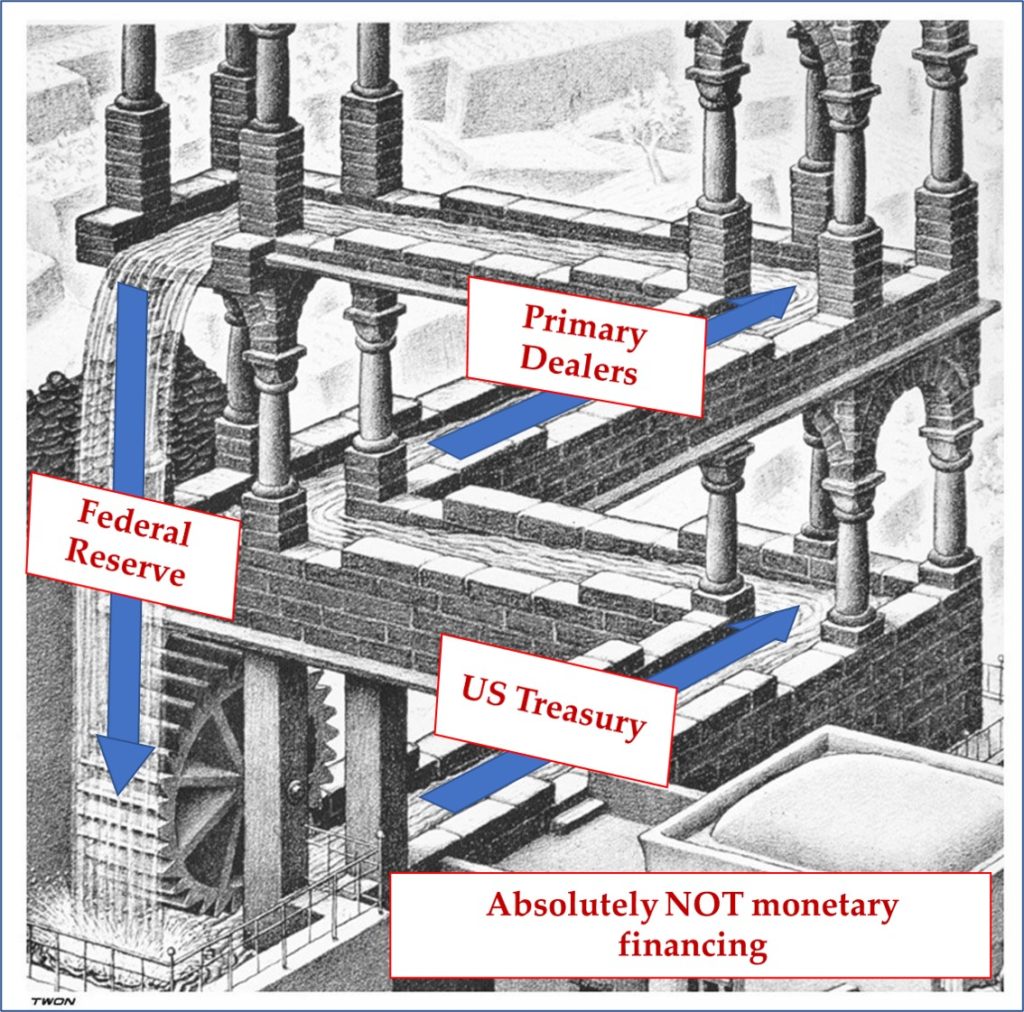

Consider, too, that in the aftermath of the GFC, for all the overt central bank assistance offered to their commercial bank charges at everyone else’s expense, vengeful regulators were also busy, strangling those same banks in layers of conflicting and costly regulation, thus greatly dampening the CBs’ influence.

Now, those banks (in much better shape, Stateside at least) are being urged to ignore those regulations which have not already been lifted and get out there and lend! Rising NPLs, less indiscriminate capital markets, and a certain reluctance to take too many risks will no doubt temper their enthusiasm somewhat. But with more and more of the heavy lifting falling to governmental agencies and with increasing underpinning from an anxious central bank, that might not prove an insuperable hurdle to overcome.

As a result, a few more dollars put in the hands of hair salons and tube-welders and a few less in those of hedge funds punting on Tesla and those good, ol’ Cantillon effects are going to be felt in a wholly different area this time around, making deflation a far less likely outcome.