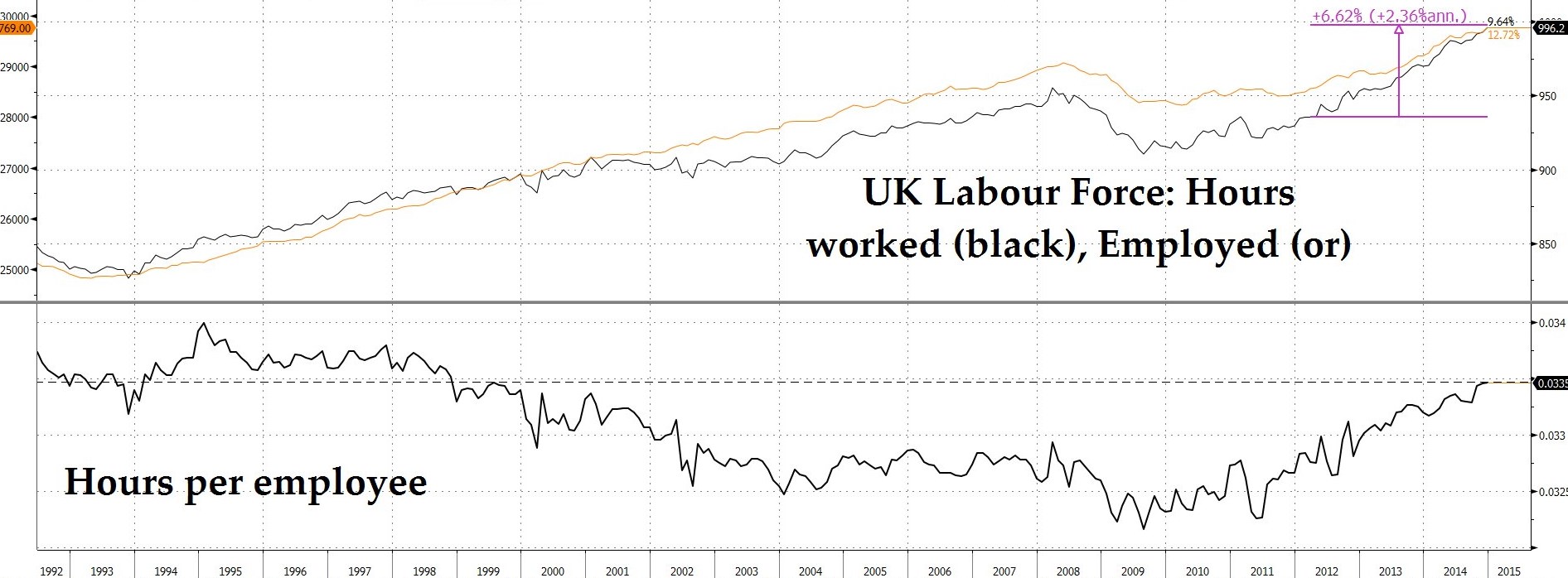

Avoiding for now all comment on the ongoing Eurozone schism, we start by taking a look at the UK where, conveniently in the run-up to the May election, everything seem to be coming up roses for the incumbents. Retail sales are strong, CBI output intentions are comfortably back inside the upper decile of the last 20 years’ readings and – perhaps most politically heartening of all – real wages are at last rising while both numbers employed and hours worked are making new, all-time highs with the ratio between the two suggesting the proportion of those working full-time is back at pre-crisis highs.

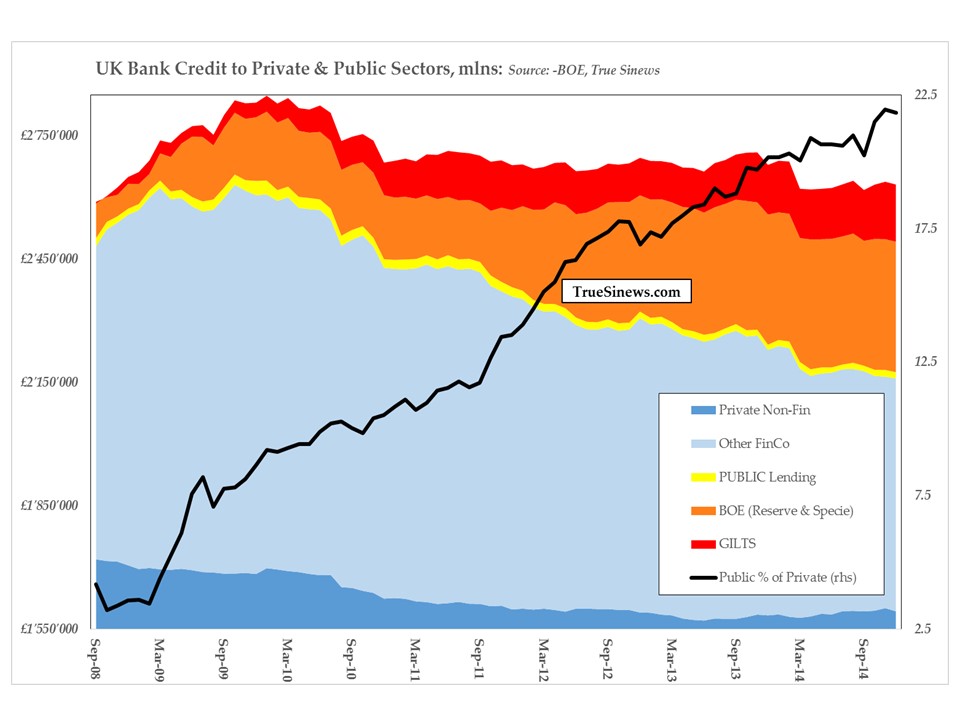

In truth, None of this is too surprising given the rapid rates of monetary growth to which we have frequently alluded – a pace of inflation (if we dare use the word in its proper sense) driven largely by the ongoing profligacy of a state which is happy to trumpet both the strength of the recovery over which it has presided and the rigorous standards of Gladstonian finance it pretends it applies despite the fact that it is still running a fiscal deficit of around £90 billion or a good 5% of GDP. Austerity, indeed!

Recalling that money is created either by central bank purchases of securities or by the granting of deposit-funded loans by commercial banks to non-bank entities, it is apparent from the chart above that the government is the most expansive sector in the country today. In fact, we can note that, in the past 2 1/2 years of rapid money growth, roughly a third of the assets on bank balance sheets which form the counterpart to their monteary liabilities take the form of either direct holdings of gilts or of the excess reserves which the Old Lady has created by means of her own copious purchases of such paper.

What is less comfortable to note is that the UK patently possesses a full-employment current account balance which is horribly in the red – as sure sign of a dreaded ‘intertemporal imbalance’ or, in more old-fashioned terms, of an excess of short-term growth which is being financed through an ongoing consumption of capital. From a level just in excess of £20 billion in the first five years of the new century to a worse position around the £35 billion mark post-LEH, the current account deficit has since deteriorated sharply to hover just shy of a nice, round £100 billion per annum.

Seen as a proportion of private sector GDP, this has now plumbed depths of -7% not seen even at the height of either the disastrous ‘Barber Boom’ of the early ’70s or of the ‘Lawson Boom’ equivalent of the late ’80s. Despite all this evidence of an all-too typical bout of overheating, the Bank of England is not signalling any urgency about when it will start to lean against such tendencies. We were even treated last week to the prospect that the oil-driven fall in CPI was being viewed with alarm, lest it lead to an ‘unanchoring’ of inflation expectations. As such, the BOE’s Maccaffrey told us, cheaper fuel was likely to postpone a response yet further into the future and bottlenecks in non-oil goods and services, go hang!

In a world of negative interest rates, yawning basis swaps, and the search for safer havens than exist in the Eurozone, it is particularly hard to know when Britain’s foreign lenders will first start to view the mix with sufficient disquiet to stop funding that gap quite so readily (thus sending sterling into a tailspin). The fact remains, however, that they will eventually do so unless either the Chancellor or the members of Fred Karney’s Circus meanwhile act to forestall the dangers. Alas! Ambient temperatures in the Seventh Circle are likely to be sub-zero before that will be the case.

Whether the market takes all this to heart is another matter for what is clear is that sterling has begun to trade in lock-step with gilt prices while those latter are also showing signs of having broken the trend which has encompassed their long ascent.

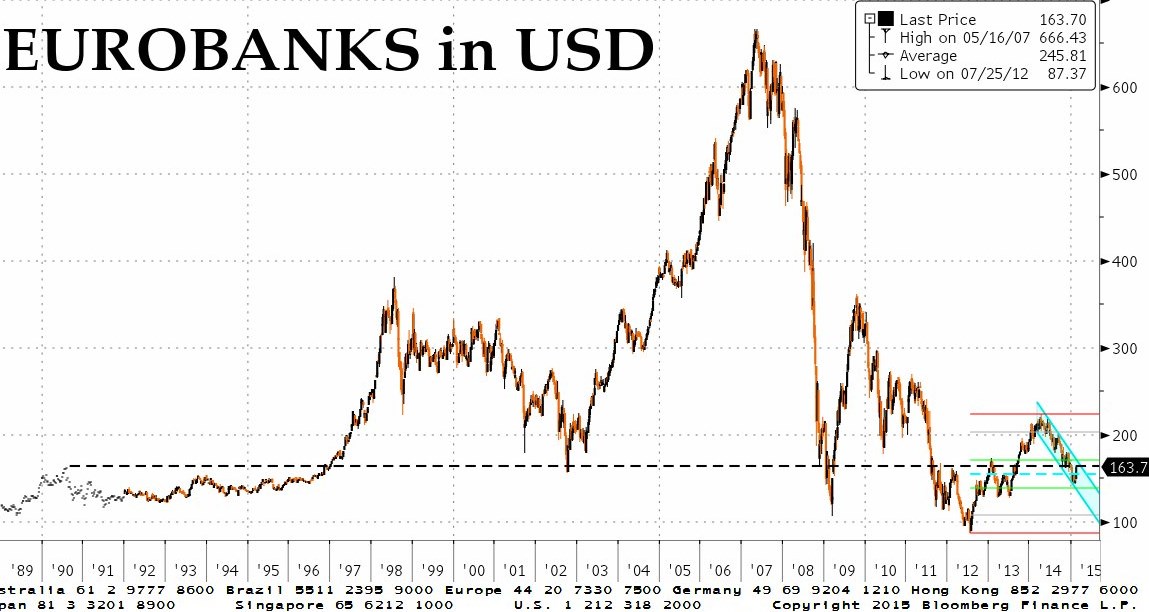

In Europe itself, all still revolves around the twin questions of whether Syriza will bend the knee and to what extent either their plucky resistance or their crushing subjugation will invigorate the ‘populist’ parties in Greece, France, and Spain. Until such time as the matter is resolved, the pressure on the non-Euro neighbours will only intensify, leading them all in turn to toy with monetary quick fixes whose longer-term consequences are truly unfathomable.

Negative interest rates are, after all, an abomination which will not only weaken the very same, sickly banks whose restoration to health has been a major goal of policy – whether by further compressing net interest margins or by destabilizing the retail deposit base upon which the regulators would like them to become far more reliant – but which are also causing palpitations across the financial universe, not least for pension and insurance companies.

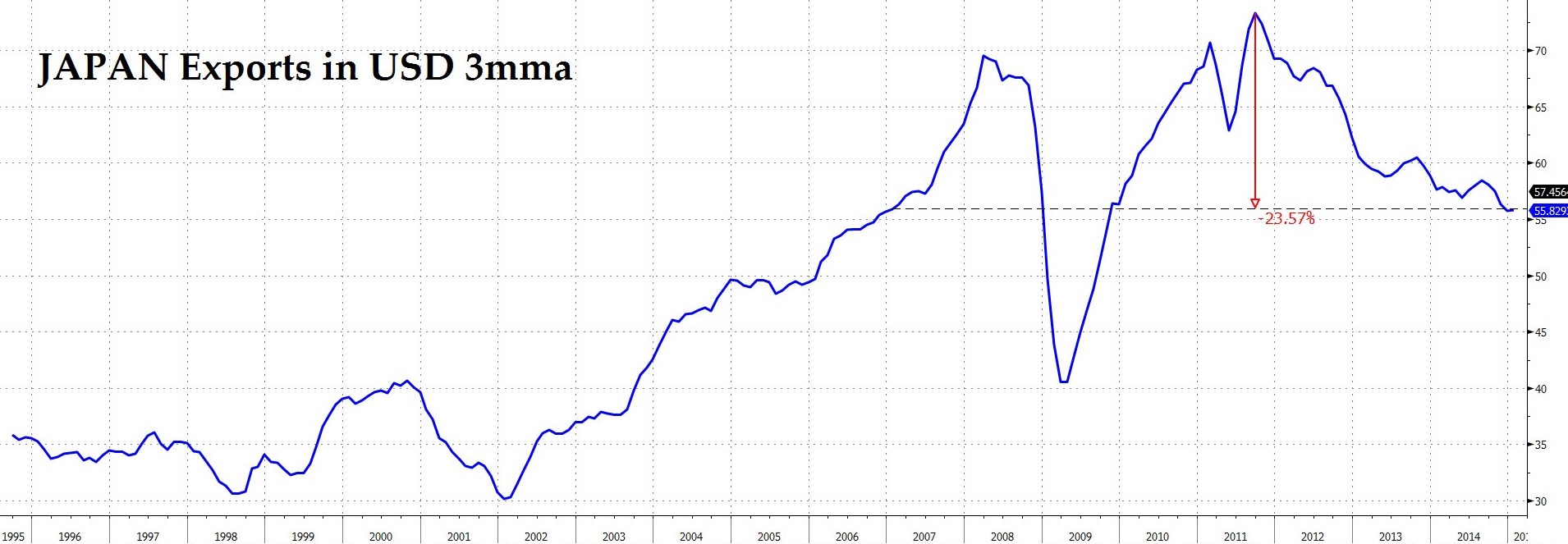

Further afield, there have been renewed attempts to assert that Abenomics is finally ‘working’, this time predicated upon a sharp uptick in yen-denominated exports and in studied ignorance of a Nikkei news survey which showed that no less than four-fifths of the citizenry had felt absolutely no tangible improvement in their lot thus far.

Setting aside that mindless brand of Mercantilism which sees a devaluation-aided firesale of a people’s goods to grateful foreign customers as a route to prosperity (a common delusion which a quick refresher course in one’s Bastiat should be enough to dispel), we find instead that, when measured in dollars, yen exports are back where they were 8 long years ago, almost a quarter below their 2011 peak. Worse, the cumulative deficit of $370 billion racked up during the past four years has sufficed to wipe out all the preceding surpluses back to 2004. Now, Japan still possesses an enormous hoard of foreign assets – a stockpile whose yen value has also been artifically boosted by Kurdoa-san’s actions – so their owners will not be on their uppers just yet. Nonetheless, we are now adding capital consumption abroad to the woes being endured at home here, too.

No wonder, perhaps, that for all the false sheen of its home currency rise, the Nikkei has seriously underperformed the S&P – a lag which may yet widen a further 25% or so before the move reaches its climax.

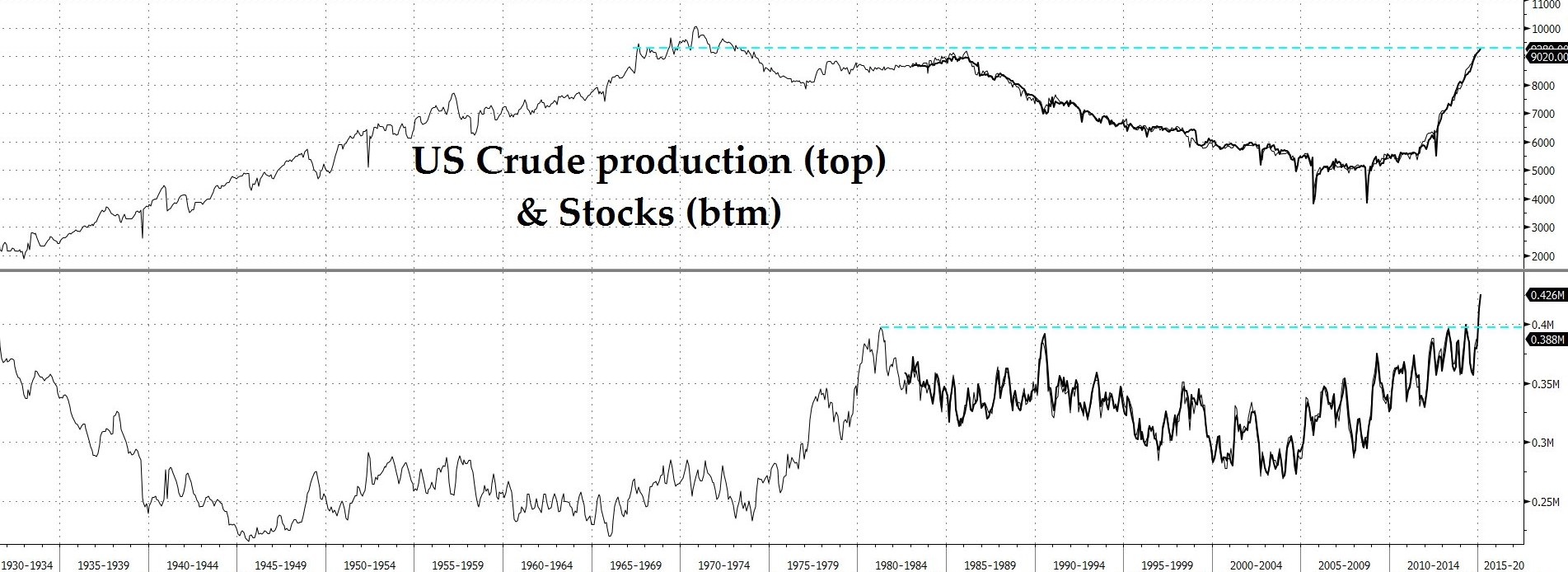

In the US itself, a certain nervousness has crept in as the recent data has tended to disappoint. To what extent this marks some genuine contagion from the contraction being experienced in the oil patch and to what degree it merely represents a hiccup occasioned by a re-run of last year’s fierce winter weather, only time will tell.

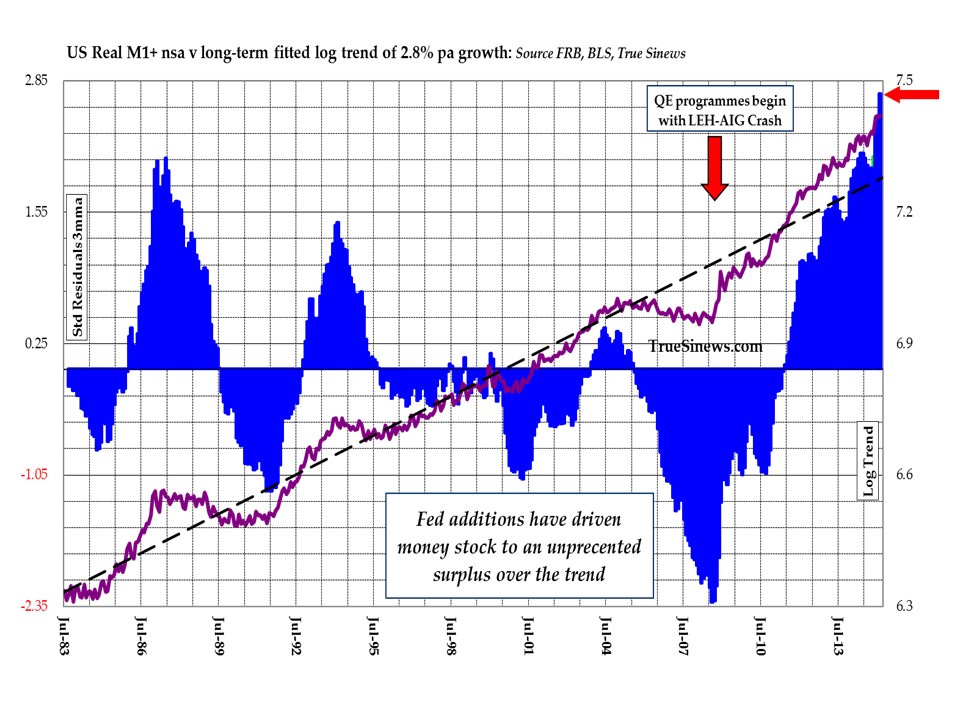

One thing is for sure, we cannot blame any undue deceleration in money growth for the so-far mild retardation in the real-side numbers. To the contrary, our favoured M1+ measure has been setting new records of deviatoin from trend these past few months, even as the monetary base itself has hit a one year low thanks to the diversion of several $100 billions in excess reserves to reverse repos and term deposits held by the Fed.

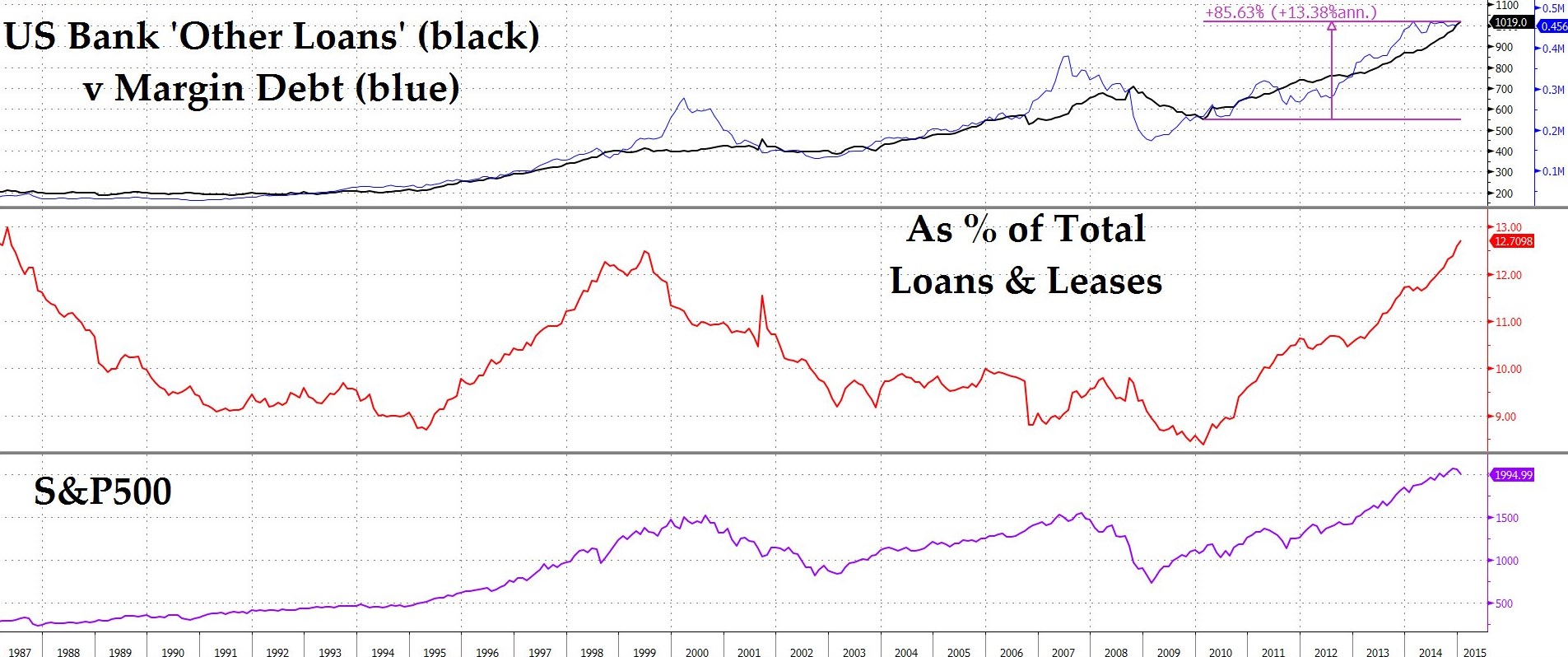

The fact that ‘inside’ money is finally outgrowing the ‘outside’, central bank kind might argue that a major phase shift is underway. Certainly, stock bulls can continue to take heart that, no matter how stretched the ‘fundamentals’ are in danger of becoming, banks are still feverishly adding to the ‘other loans and leases’ line entry wherein resides their contribution to outstanding security credit.

The fact that ‘inside’ money is finally outgrowing the ‘outside’, central bank kind might argue that a major phase shift is underway. Certainly, stock bulls can continue to take heart that, no matter how stretched the ‘fundamentals’ are in danger of becoming, banks are still feverishly adding to the ‘other loans and leases’ line entry wherein resides their contribution to outstanding security credit.

Thus, though one cannot help feeling we are approaching the home straight in the long rally in asset markets – not least in a bond market which gratifyingly delivered a sharp, 50bp back up in yield from our suggested culmination point of 2.20% for the 30-year – we can read the stock chart as allowing us the possibility of another 17% or so of headroom, split perhaps as to 10% straight stock appreciation with a remainder of 7% coming from another round of dollar strength.

As for the move into European assets which has helped bolster the single currency of late, we would note that if the Eurofinancials are as depressed as we earlier saw they were, and if the broad index is as high as it undoubtedly is, by implication all non-finacials must be becoming fairly fully valued already.

All told, we would hestitate to call for a complete reversal of favour vis-a-vis the US market just yet, at least in equities, as here:-

or in the currency, as here, and for as long as that trendline break holds good:-

Where there is just a glimmer of hope is in the bond market, where relative returns have shot to the top of a well-defined distribution and so offer a trading chance to play for an eventual mean reversion using the neatly delineated stop which lies just above current levels.

With Bund yields a paltry 35bps and given a view on the currency which does not yet envisage a renaissance in the euro, such a move can only really come from weakness in the US bond market. We do have the chart pattern to suggest this already, nor would it take much for back-month eurodollars to break trend in confirmation.

To fully lay the Ghost of ’37 and thus to allow fixed income to weaken further might, however, take more than the likes of James Bullard warning us that we have not priced in a steep enough trajectory of impending rate hikes.

That leaves Madame Chair herself to say something hawkish in her testimony this week or else we will be back to waiting to see what happens to US indicators once the Big Freeze finally dissipates. Hanging on the words of a central banker or acknowledging one’s dependence on the vagaries of the weather: I’m not sure which is worse.

Good hunting!

NB The foregoing is for educative and entertainment purposes only. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting investment advice. All rights reserved. ©True Sinews