On April 13th, a financial pundit with a wide media following made the following (loosely transcribed) proposition about US banking stocks: Banks won’t rally because rates -long and short- are too low; Japan is our marker – banks there falling while their US/EZ peers rose pre-GFC and have not made any ground since; vis-à-vis their EZ peers, US bank returns have long been anomalous, ergo their out-performance won’t be repeated. We demur in the main.

We began our response with the rejoinder that banks make money by increasing charges – and where possible spreads – the first to compensate for any absence of Net Interest Margin, the second to try to maintain it.

NB: When long rates are artificially suppressed & flattened to or through 0%, opportunity costs between various forms of financial holding vanish and demand for money -as a savings medium, not as a transactional tool – RISES. This confuses much financial analysis, particularly on the part of those hewing mechanically to concepts such as monetary ‘velocity’ and the infamous MV = PT relation from which this is derived.

It wasn’t low rates per se that held Japan banks back, post 1989, but scattered failures and an heroic total of write-offs and restructurings of their toxic, bubble-era legacy – something which helped the country’s eventual, creditable real per capita GDP recovery.

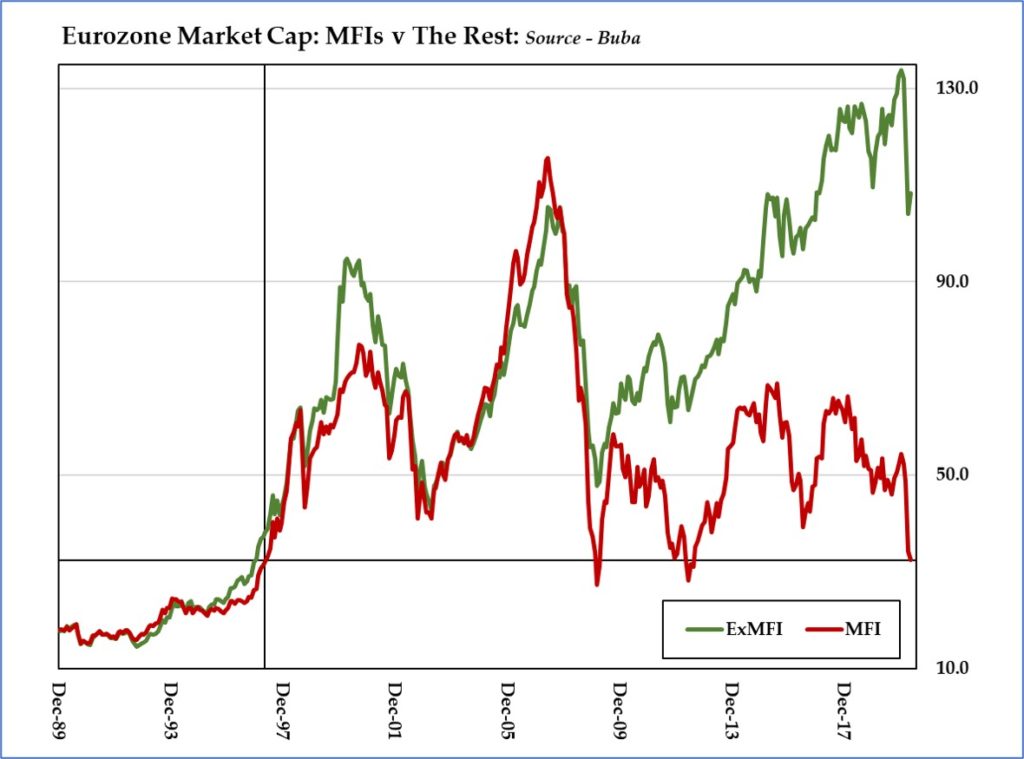

In contrast, in the EZ and the US, the deliberate laxity of monetary policy (a) to paint lipstick on the pig of the newly-launched euro and (b) to overcome the Tech Bubble & 9/11 saw many illusory profits earned in the first decade of the new millennium, ‘profits’ which evaporated retrospectively in the GFC bust, as was only just.

Since then Japanese banks, if unexciting as investments, have continued to reflect a thankfully reduced role in society, reminding us that finance is a means, not an end!

In terminally overbanked Europe, by contrast, under the ECB’s horribly politicised management and in thrall to the EU’s strangling bureaucracy would probably have been zombified, NIRP or no.

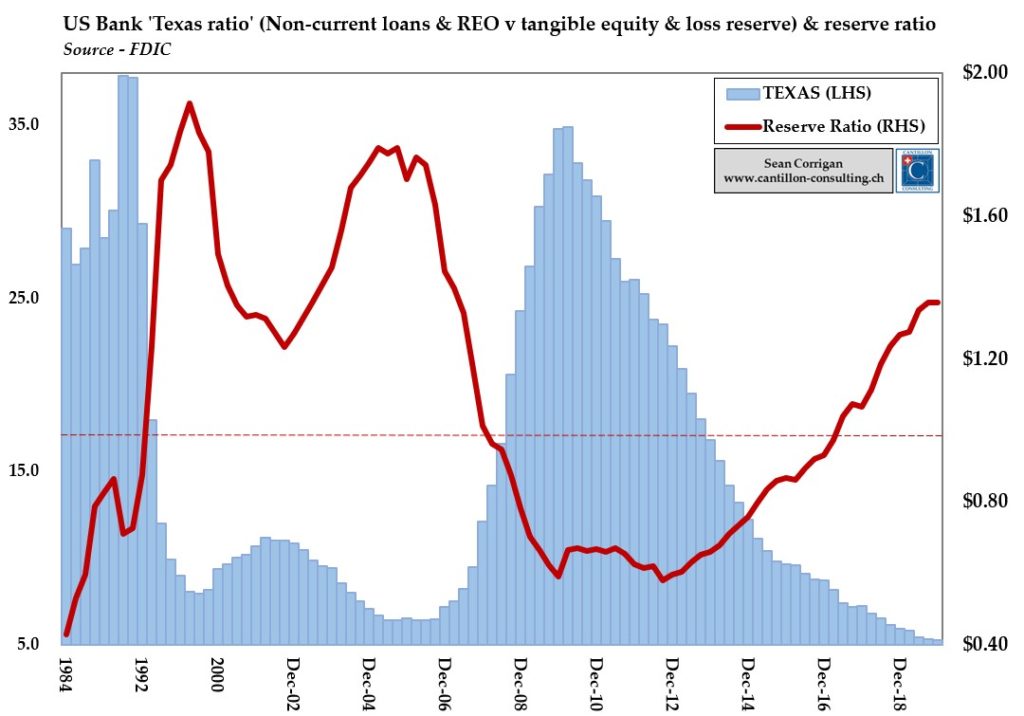

The US, however, as a place where the bank restructuring made necessary after Lehman’s collapse, was, in good part, carried out – if partly by allowing the Too Big To Fail to swell into the Too Bigger To Fail. Countless to-be-revealed horrors no doubt lurk elsewhere but, ostensibly, balance sheets went into lockdown in their best condition in decades (FDIC, qv).

Japan as our economic pathfinder? Perhaps. After all, well-noted societal differences may not entirely outweigh both economic law and commercial logic but it also depends on the degree to which the state in other countries will step back, post-pan(dem)ic – something about which must be cautiously pessimistic.

Does the Japanese example mean US banks are doomed to follow the same course into relative stagnation? We shall see. But one must wonder whether the ‘Banking Trust’ in the US is perhaps still too powerful to let itself wither so passively on the vine.

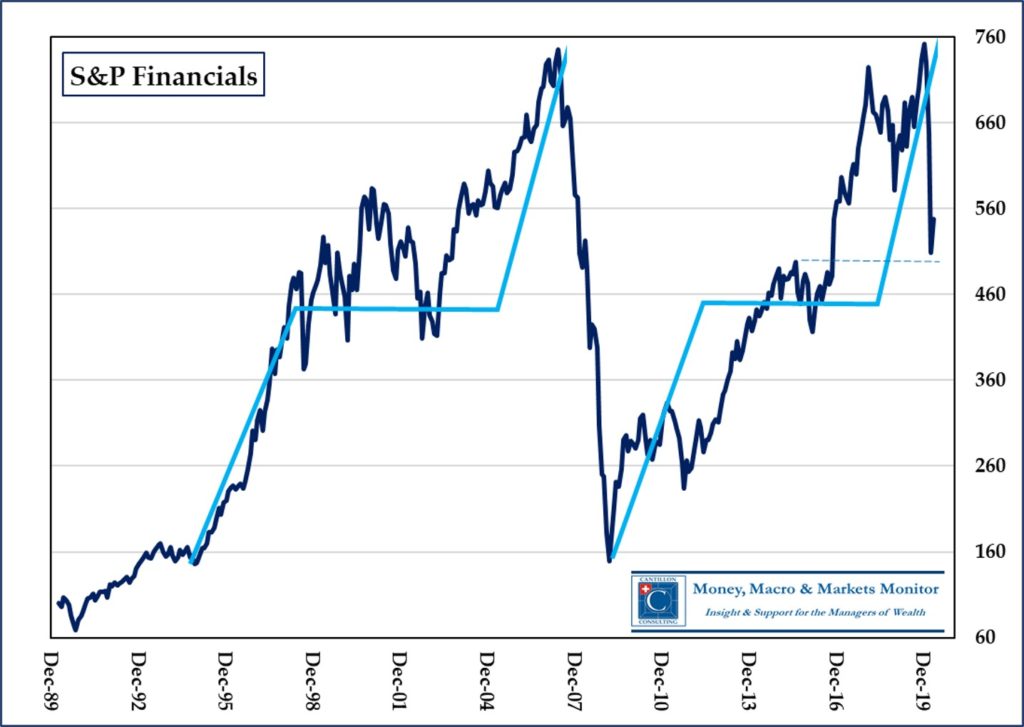

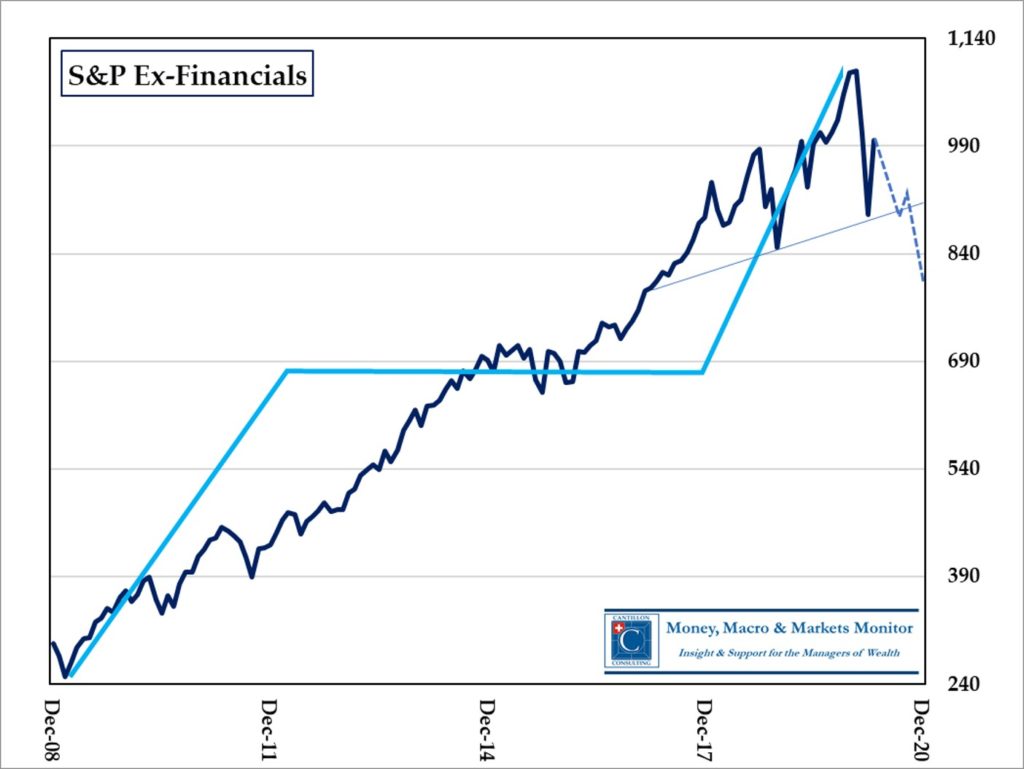

Certainly, with dividends being frowned upon and untold NPLs to overcome, there is merit in being cautious. We might draw comfort from the fact that the pre-LEH highs were regained just before we went over the cliff again this spring, despite ever lower rates across the curve and out the credit spectrum. Conversely, that coincidence might also worry us whether they will also repeat the subsequent plunge, given the self-similarities in their price history.

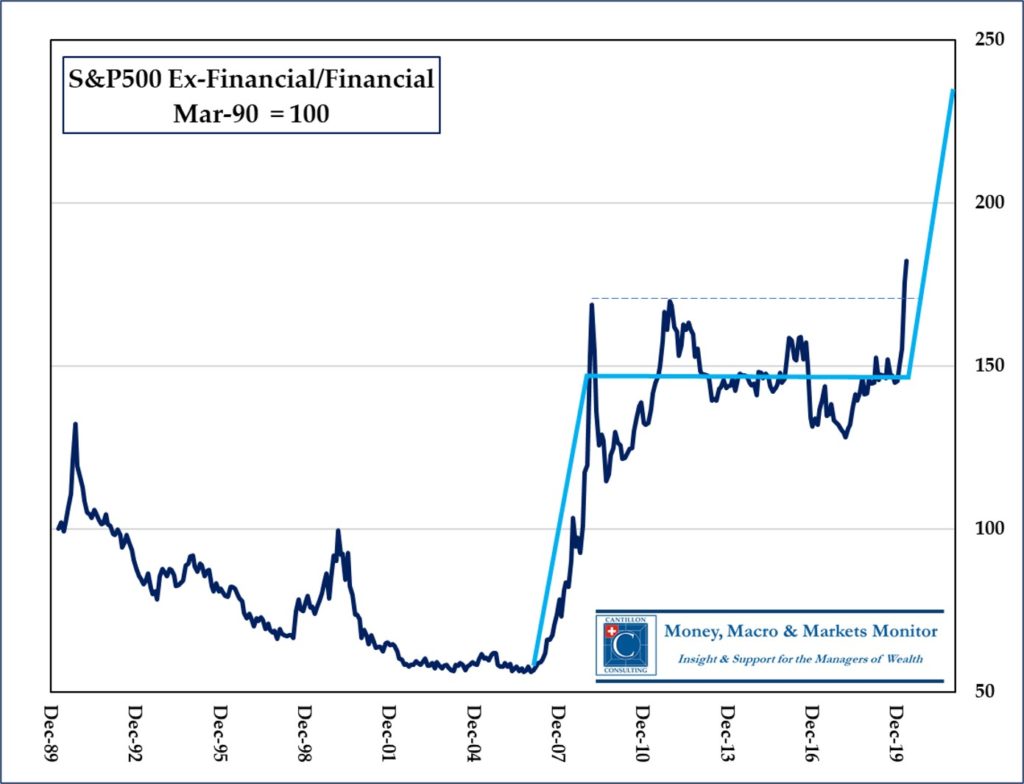

Last time, too, US financials retreated markedly from record high valuations vis-à-vis their non-financial peers, and the ratio between them seems to have broken out of its intervening range, so, the idea that US banks they are best avoided for now is something not to be too fervently disputed.

The rising tide (of panicky Fed intervention) may lift all boats, but banks carry a particularly heavy anchor of Rumsfeldian Unknown Unknowns with which to limit their buoyancy.