Another ‘surprise’ which is all but given is that the upcoming UK election is uniquely poised to confuse all those who affect to practice the dark arts of psephology. By way of a brief synopsis, the state of play, with just over four months to go to polling day, is as follows.

After their triumph in the European elections elevated them from fringe party to serious contenders, UKIP have both weathered a storm of establishment black propaganda as have largely succeeded in shrugging off a welter of gaffes and inopportune remarks from within their own, mostly inexperienced ranks to stand out as the prime threat to the routine political arithmetic of England. While conventional wisdom has them likely to undermine that prime example of a Man Without A Chest, David Cameron, by prising away the anti-EU right from its uneasy roost among the Tory ranks, it is also possible that Nigel Farage’s team could tempt large numbers of what used to be called Mondeo Man – working-class males only just to the left of centre – to abandon the hapless Ed Miliband’s Labour.

With the Liberals having sacrificed all identity as the price for agreeing to enter a coalition with a party which their grass-root members abhor, the metropolitan tree-huggers and sock-and-sandal recyclers who make up their core following may well go the whole hog and vote Green instead of Orange this time around and so cast leader Nick Clegg unceremoniously onto the scrapheap of ambition.

Meanwhile, opinion polls north of the border show that Scottish voters are already ruing their poltroonery – or gullibility – in allowing Westminster’s weasel words to talk them out of making a stand for rugged self-reliance in their recent referendum. With the SNP surging from 20% to 40% of the prospective vote as a consequence; with Labour collapsing from 42% to 26%; and with both Liberals and Tories slipping ever lower in the rankings, an even distribution of such putative support in May could cost our Ed’s Tartan Army three quarters of their 41 seats while catapulting the nationalists – with more than a dash of irony – to the status of third largest party overall and hence crowning them as the ultimate power-brokers in what would almost definitely be a hung – but probably a red-tinged – parliament.

The chaos which would ensue is only to be imagined since the SNP is heavily pro-European (better to be dominated by Brussels than by the Auld Enemy, one presumes), yet, come the count, a sixth or more of the electorate may have supported the avowedly secessionist UKIP together with that substantial body of voters from the main parties which makes up the roughly 50% share the pollsters tell us want to quit the EU at the earliest opportunity – a stance apparently shared by no less than nine of Cameron’s cabinet colleagues, by the way.

Not only that, but such an outcome would immediately raise tensions regarding the so-called West Lothian question, i.e., the circumstance in which a notionally separatist Scots MP gets to cast his vote on all matters of purely English (or Welsh) concern while his southern counterpart has only a limited say in return on what is decided on the other side of Hadrian’s Wall. Not such a big deal when there were only 6 SNP members in the House and the other 53 from beyond the border took the whip with one of the mainstream trio, but a little more fractious when 40-odd would-be William Wallaces are using the coalition process to advance the cause of independence by all means at their disposal.

If Britain actually had a constitution, this set-up would clearly deliver it into a state of crisis. It might even trigger a broader realignment, with the Tory wets and the Blairite wing of Labour finding common cause; the hard left snuggling up to the Khmer Verte (the Greens) – along with the last, lingering rump of the Liberals – and the Tory ‘bastards’ forming a new Eurosceptic vanguard with UKIP.

The question then must be asked, how well situated is the country – economically speaking – to endure such a vigorous test of its political institutions?

To this observer, the answer would be ‘not very well, at all.’ Britain, you see, is rapidly sliding back into its bad old ways of spending too much, saving too little, and all the while allowing the state to loom far too large in people’s affairs, bolstered by the fact that far too many members of the populace are loth to give up their long-accustomed habit of trying to live at their neighbours’ expense and of borrowing from abroad whatever dole transfers the state cannot raise in taxes at home.

Let us start with the latest economic round to see what we mean. Though hours worked in the UK, along with both overall and private sector GDP, are each enviably some 3-5% above the pre-Crash peak – a constellation of which many Eurozone countries can still only dream – this has come about only through a 7-year reduction in real wages of a cumulative 11%.

Pricing people back into jobs this way is one thing – if decidedly more unfair on all the other innocent victims of the Bank of England’s inflationism than would have been a simple pay cut – but it is also significant that, having trended up at around 2.3% per annum for almost four decades, real GDP per hour worked has shown no improvement whatsoever since Northern Rock closed its doors, seven long years ago. If we add in the fact that the UK has officially seen net inward migration of 1.5 million people in that same period, we can perhaps see how much of that growth has been achieved – through the blunt instrument of adding a big slug of low wage, low output, imported labour to the mix.

Sadly, Fred Karney’s policies of determined monetary laxity have added two malign side-effects to the short term boost to growth for which they are so widely praised. Firstly, the combination of Gilt-enacted QE with near zero interest rates has loosened the constraints on a state sector which still routinely spends a sum equivalent to almost one half of private GDP, with around a sixth of that being borrowed, even now amid a recovery vigorous enough to elicit a full measure of George Osborne’s headline-hogging boastfulness.

Alarmingly, too, the punishment of savers and the encouragement of borrowers has reached a point where households have become net debtors at the aggregate level for the first time since the GFC while, simultaneously, non-financial corporates have collectively swung into the red for the first time since they were borrowing to relieve Culpability Brown of his pricey mobile phone airwave licences, back at the height of the Tech Bubble.

Mortgage debt is rising by £20 billion a year, consumer credit by £10 billion (the most since late ’08), student loans by £7 billion. Disposable income grew £29 billion in that same time which means debt:income may be swelling once more, from a point still north of 130%.

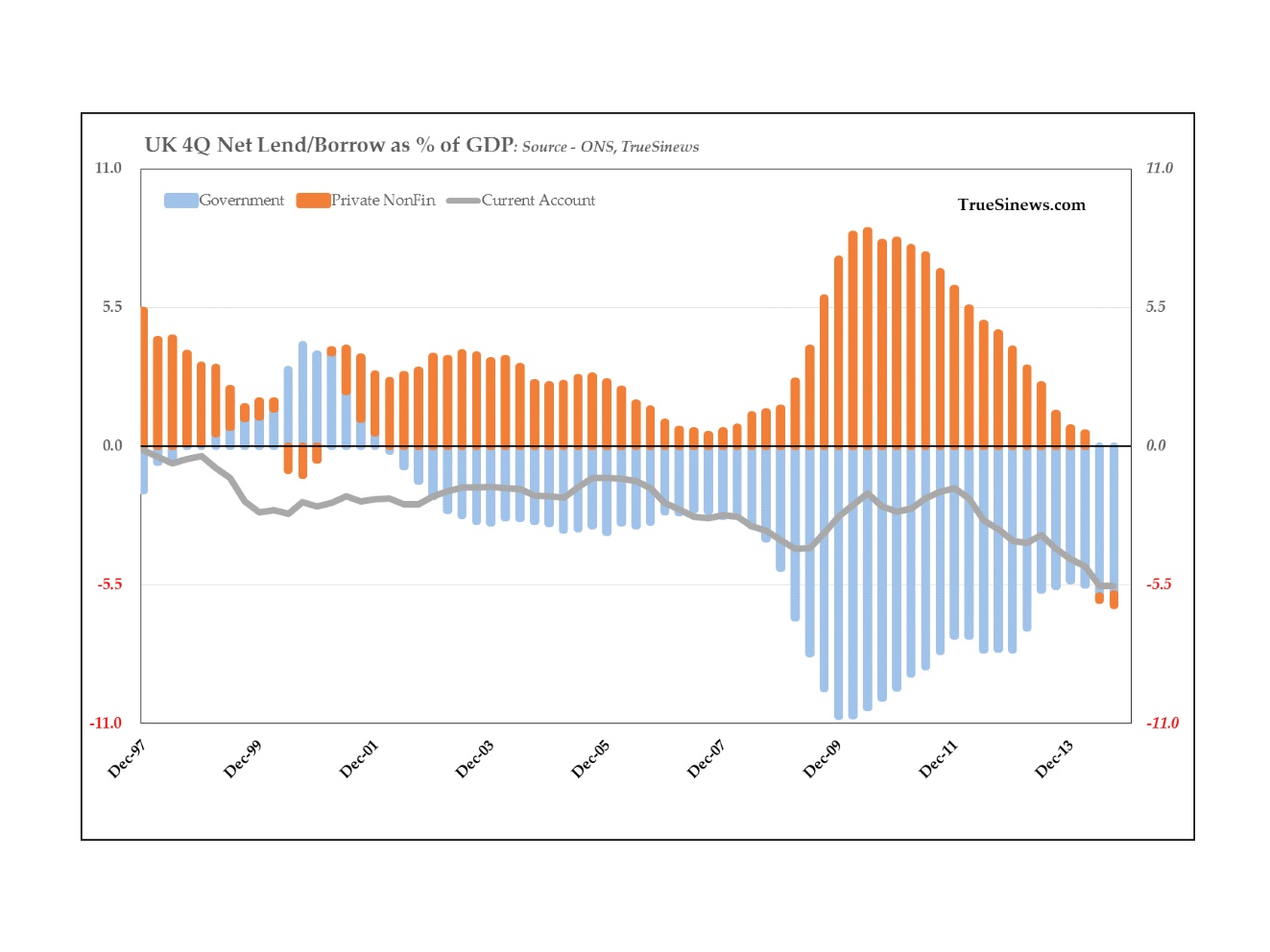

As a result, while state prodigality has diminished from its peak deficit of 10.7% of GDP (seen between QI-09 and QI-10) to today’s 5.9%, the non-financial private sector has gone from a point where it was saving 8.8% (and so funding four-fifths of Leviathan’s excesses) to a point where it, too, is now looking for 0.5% of GDP for its own consumptive purposes (all figures 4Q moving averages).

No wonder then that the current account deficit has blown up to a six decade high of 6.0% of GDP, despite the co-existence of a record surplus of 5.1% on the service account (the arithmetically astute will quickly infer that this must entail a similarly swingeing deficit on visible trade – a shortfall which in fact stretches to a hefty 7.1%). For comparison, when Chancellor Dennis Healey suffered the ignominy of appealing to the IMF for help in 1976, the balance of payments was only 1.5% in the red (though the tally had briefly hit 4.3% a year or two before, in the immediate aftermath of the first oil shock).

In fact, if we only look at the latest reported data – those for QIII – there is a chance that the BOP number may be revised to yet a deeper nadir since, in the three months to September, the ONS presently estimates that the public deficit was 5.1% of GDP, while households borrowed a six-year high balance of 2.6% of GDP and corporates took up a 14-year high credit of 2.2%, making for an aggregate shortfall of no less than 9.9%. Subtracting a net positive contribution of 0.2% from the domestic financial sector, that still leaves 9.7% to be financed, in theory, from foreigners and thereby to determine the scale of the current account deficit.

Performing the calculation in a different manner, the UK government has borrowed £109 billion ($167 billion) in the twelve months to September, an overspend which has leaked almost entirely abroad and has thus required a £98 billion ($150 billion) contribution in goods sold on credit from the world beyond Albion’s shining seas.

So, let us forget for a moment the controversy over the gaping hole which persists in the government’s finances and the laughably misnamed policy of ‘austerity’ which the regime has adopted to try to deal with this. Instead, let us lift our eyes to a horizon beyond our shores and we can surely agree that the sum of £130 a month per capita is not at all an unimpressive pace at which to be adding to a net external deficit of £450 billion (25% of GDP) or to an ex-FDI gross liability of £8,840 billion (490% of GDP), against which mountain of potentially nervy obligations the Treasury disposes of a defence against a classic ‘sudden stop’ of a paltry £63 billion in gross and only £26 billion in net FX reserves (equal to around three weeks’ worth of goods imports).

Thus, not only is a full-employment Britain a country which must run an unsustainably large external deficit (since it is already setting records with 6% of the workforce still out of a job), but it has again been seduced into being one where all sectors are borrowing, not saving, largely in order to finance present consumption, meaning it is prey to a rather nasty, Hayekian ‘intertemporal’ disequilibrium – the cardinal economic sin of enjoying overmuch jam today at the cost of jam foregone tomorrow.

One day the piper to whose shrill accompaniment we are now dancing our merry jig (our Chuck Prince Charleston?) will present us with a bill which we are unlikely to be able to meet absent a great deal of sacrifice and possibly not without suffering a veritable collapse in the value of the currency to boot.

So, surprise number two? Shortly after the election is held, that migrant cuckoo of a central bank governor will be off and away, back to his native Canada to ready his own political promotion – either by reinforcing the governing team if Junior Trudeau’s Liberals triumph there in October or perhaps by taking over the leadership should the latter fail. One thing of which we can be fairly sure is that he will not hang around long to see a political melt-down in Britain mutate into a full blown sterling crisis and so add a few unsightly blots to his heretofore Teflon-coated escutcheon.

NB The foregoing is for educative and entertainment purposes only. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting investment advice. All rights reserved. ©True Sinews