Reuters’ story that SAFE told its banks they should be as obstructive as possible in meeting customer demands for foreign currency, but should absolute not divulge the reason why, certainly succeeded in causing a stir in markets.

A basic economic precept says that each added quantity of a given good becomes less and less valuable to potential owners: conversely, each removal can only raise people’s estimation of whatever remains. No less true of foreign currency than it is of cigarettes or soybeans, if Beijing really was determined to stop the efflux, it would allow it to reduce the supply of saleable renminbi, thus raising the cost for those wishing to sell short as well as making existing yuan balances a progressively more attractive proposition to retain.

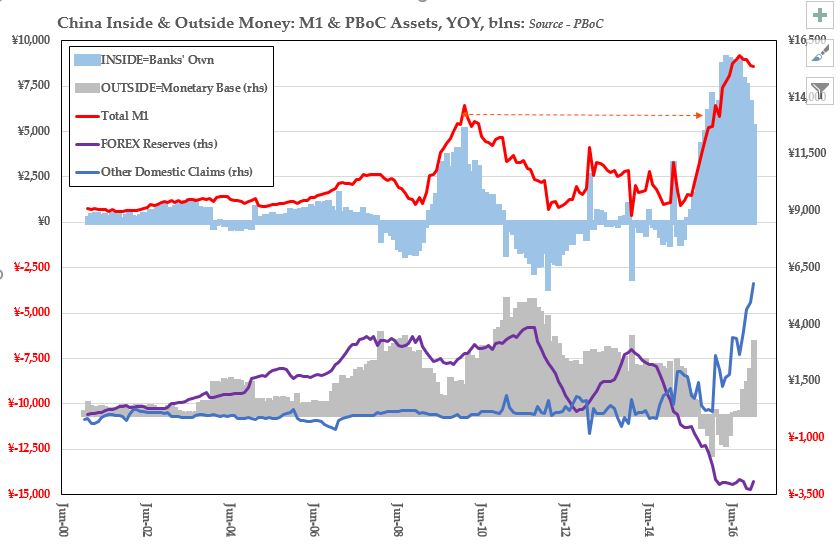

A short while ago, it was a widely held – if demonstrably erroneous – contention that the PBoC’s heavy reliance on foreign exchange as the bedrock beneath the inverted pyramid of Chinese credit made the system uniquely vulnerable in the event that the nation ever ran a deficit on either the current or capital account (a consequence which lies at the very core of the classically self-governing process known for three centuries as the ‘specie-flow mechanism’).

The truth is, that far from retarding its creation, the oft-discussed foreign exchange drain has been accompanied by one of its most rapid rates of increase of new money (as well as one of the fastest rates of acceleration) to be found in the modern record.

Forex reserves peaked out at a whisker under $4 trillion in June 2014 and as they first gurgled away, the increase in M1 slowed to a crawl of around 3%YOY. Then, one year and some $300 billion later, as that year’s stock market bust was just beginning to engulf a new batch of hapless speculators, the floodgates were once again opened. Even as forex continued to dwindle, the central bank became engaged in a concerted effort to re-boot the credit creation mechanism.

In the 18 months since, another CNY4.8 trillion in those reserves ($700 billion by the alternative count) have evaporated. Simultaneously, the PBoC has deployed a whole host of counter-measures causing ‘claims on depositary corporations’ to explode, their CNY7 trillion gain helping to expand, not contract, the monetary base (from its local minimum in May, the last seven months have seen a 19% annualized gain in the measure). Further, it has driven such an impressive rise in the money multiplier that M1 itself has swollen by close to 40% (CNY13.6 trillion).

Scarcity has hardly been the issue and with the obvious domestic outlet – property – choked off by administrative fiat and with much of heavy industry presenting a less than compelling investment case, commodities, Bitcoin, and foreign assets have therefore been the media of choice for a people determined to disembarrass themselves of their surplus renminbi.

Despite official denials of complicity, this goes to show that you can get as much depreciation of your currency – internal and external – as you are willing to pay for and that, so far, the PBOC has indeed been all too willing.