For all those still clinging to the hope that today’s extraordinary level of equity valuation will soon reverse and what we fondly remember as ‘normality’ will again break out (and we confess that we are often to be found among their camp), we and they should never lose sight of the fact that this exaggeration is a direct result of the central banks’ deliberate move to destroy the market for time discount and so to provide the rentier class with a little assisted suicide (only fair since it was obviously all the savers’ fault that the previous period of central bank laxity had induced far too many people to borrow too much bank credit the last time around with predictably disastrous results).

Alas, the corollary to this select form of ‘inflation’ (a much abused term about which we shall have a good deal to say in these pages) does not necessarily apply – or at least does not apply in quite such a regular manner – to those so-called ‘real assets’ among which investors may also seek some respite from the grinding impoverishment of below-zero real interest rates. This disparity occurs for the simple, but oft overlooked reason that the very same processes which first elevate the price of such ‘assets’ also both stimulate and facilitate the laying down of the means with which to produce more of them and so alleviate the scarcity. No cure for high prices like high prices, as the old adage goes.

Though this latter evolution takes time to bring to fruition, that it does indeed come about should come as no surprise to devotees of Austrian Business Cycle Theory. In its barest essentials, the one thing this thesis insists upon is that a market rate of interest which is too long depressed below the (admittedly unobservable) ‘natural rate’ (the one which reflects actual societal time preference in deciding whether to have jam today or jam tomorrow) will lead to an unwarranted degree of capital lengthening. This build-out is usually all the more enhanced the more protracted (the more ’roundabout’ in the original parlance) are the associated cash flows, the higher therefore their duration or – put another way – the longer they take to amortize and the project to deliver its anticipated returns. Long bonds, as any yield jockey will tell you, rally more than short for any given rate change: ‘long’ industrial chains do exactly the same.

Given this, the aggravated effects on resource industries should be easy to imagine. What, after all, could be more ’roundabout’ or more capital-intensive than a deepwater offshore oil rig, a floating LNG platform, or a new copper mine built in the previously trackless wastes of the virgin jungle?

So it has traditionally been the case that the extractive industries routinely fall prey – about every generation or so – to a tremendously extended hog cycle, or perhaps to a Lotka-Volterra predator-prey dynamic of near great extinction magnitude.

Working from the other direction, periods of enhanced resource scarcity caused by war or deliberate supply withholding (e.g., the two oil shocks), or of the kind of elevated resource pricing which has come about through monetary disruption (and the two can often go merrily hand in hand) have often been those most unpropitious for stock prices, not least because the heightened uncertainties involved in pricing, budgeting, and accounting typically crush multiples even if nominal earnings do keep pace with what are (in the latter case) typically swollen nominal revenues.

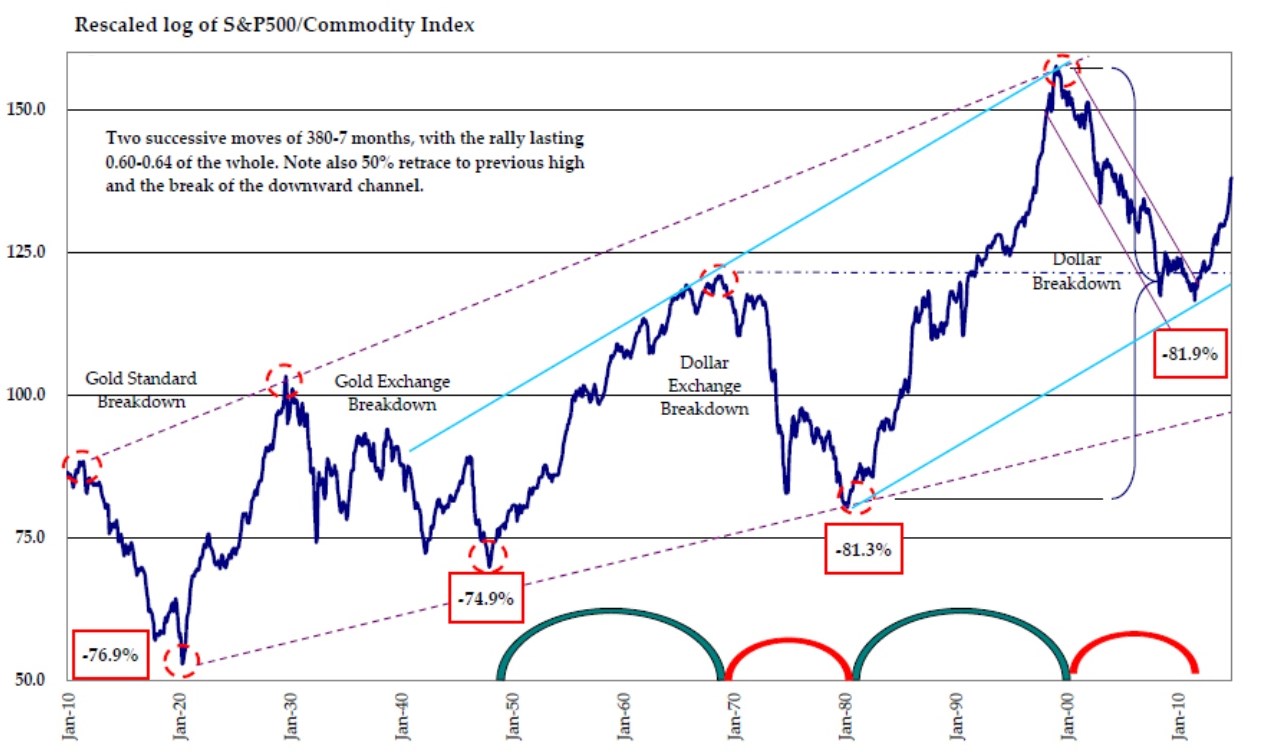

Thus the ratio of the prices of equities and those of commodities has chased itself up and down some pretty vertiginous hills and valleys, laid out along a consistently rising trend, as can be seen from a graph of the relation between them over the past hundred years or so.

Equities were at their weakest (and commodities their strongest) at the end of the Great War, only to move sharply in the other direction in a period bracketed by the sharp, purgative deflation of 1920-21 and the Wall St. Crash of 1929. Falling in a wavelike manner through the Depression and the Second World War, the ratio bottomed out in the 1949 inflationary slump before again climbing onward through the Go-Go 50s and 60s to a peak which coincided with the first inkling of the coming breakdown of the Bretton Woods system.

The Great Inflation which followed as currencies floated and still-dirigiste governments attempted to ride the fiction of the Phillips curve took stocks to another nadir and commodities to a steepling zenith at the end of the 1970s when a certain Mr Volcker – backed up by Chancellor Howe in the UK – helped rewrite the rulebook for all.

Another two decades of equity glory and commodity dismay were to follow, culminating in the oil price slump of 1998 and the soaring Tech bubble peak of 2000.

Cue another reversal to the $150/bbl heights of summer 2008, since when the balance has gradually shifted once more with equities pushing every upward (albeit for the deplorable reasons discussed at the head of this article) while the arrival of much of that long-awaited extra supply of raw materials, at a time when the unresolved overhang of the last Boom is still throttling the entrepreneurial impulse across far too extensive a swathe of the globe, has caused a melt-down in one after another of the financial markets’ erstwhile new playthings, from cotton and rubber, via gold and silver, to iron ore and oil.

Loosely then, equities bottomed against commodities in 1920, 1950, 1980, and again in 2010. Though not quite so regularly spaced between the wars, the succeeding two relative peaks occurred close to 1970 and again, thirty years or so on, in 2000.

Roughly 10 years of ‘real asset’ bragging rights – with a fall in the stock/commodity ratio of between 75-82% on each of four occasions – have thus been interspersed with 20 years of equity triumph – a counterpoint what has, each time, set a higher high at its culmination.

If the pattern is to be repeated in full this time around, it could be another 15 years – and a whole desert of resource investing despair before the tide turns once more. Did someone at the back say, ‘supercycle’?

NB The foregoing is for educative and entertainment purposes only. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting investment advice. All rights reserved. ©True Sinews