Somewhat lost in the excitement over the ongoing plunge in the oil price, the tepid endorsement given at the low turn-out election to Shinzo Abe’s sacrifice of the pensioner to the property speculator, and the susurration of rumours that Draghi will soon admit that he has suffered the heaviest defeat suffered by a Roman at the hands of his northern tormentors since Varus lost three whole legions in the Teutoburger Wald, before scuttling back to take up his dream job in the Quirinale, the Chinese have been holding their agenda-setting Central Economic Work Conference.

Out of this august gathering, we again heard much about the policy of the ‘new normal’ – a formulation which basically entails the choking off of investment for its own sake (though the cynic might comment that a good deal of this is actually intended to be shifted to expanding FTAs and to building out the New Silk Road) alongside a greater emphasis on the quality of ‘growth’ rather than on its quantity.

While all this entails the gritted teeth acceptance of a much slower GDP increment than heretofore decreed (if still one which seemingly clings to the fabrication of a 7-point-something rate of gain), it also comes with a long wish list of structural and micro reforms – in finance, energy, agriculture, tech, and trade – of which a Brussels, rather than a Beijing, bureaucrat can but dream.

With regard to that latter issue, the avowal is that the model of the pioneering Shanghai free trade zone will be rolled out across progressively more provinces along the incipient ‘land bridge’ to the West while, internationally, these will be complemented with an expended network of bilateral free trade agreements. Coincident with this, the intent is to ‘promote balance in international payments’ – a formulation which sounds benign but which should probably best be interpreted in the context of two further desiderata, viz., that exports should ‘support the economy‘ while outbound investment should be ‘speeded-up‘.

Thus, while the first aim superficially appears to promise a narrowing of China’s vast trade surplus (a reduction of which unconscious mercantilists everywhere would unthinkingly welcome), the second plainly threatens the opposite. Thus it is left to the third to comprise the move which squares the circle as follows: excess capacity will find its way onto world markets but the sterile accumulation of forex reserves to which this has so far contributed will give way to a more active dispersal of the funds (and, presumably, to a throttling back of hot money inflows) so that a higher net goods outflow will be offset by a magnified series of capital and financial outlays.

If our interpretation is correct, one can therefore expect much ongoing anguish about China ‘exporting deflation’. This despite the fact that, under the workings of our present ‘childish game of (monetary) marbles’ this expression is meaningless. Since the emergence Country A’s trade surplus cannot currently effect a permanent reduction in its deficit-counterpart B’s own stock of money and credit, it can only shift relative prices slowly against itself if it the accounts are squared by the more urgent selling of B’s currency for A’s on the exchanges; or it can leave them broadly unchanged if the money is instead willingly lent back or exchanged for other claims on B; or, conversely, A can import inflation if the central bank there insists upon converting all such receipts into local currency and it then leaves the addition to circulate against an unexpanded stock of domestically-available consumption goods.

Of the three options, the first would seem to be ruled out as not involving any ostensible ‘balance’, while the last is the mechanism – with the added overlay of a good deal of semi-legitimate, ‘hot’ financial influx – which has characterised the policy now forcibly being repudiated. By elimination, that can only mean we are most likely to resort to option two, that is to say we experience a chronically positive trade gap (one which the present fallen price of crude and its products, operating on China’s ~6Mbpd appetite for net imports thereof, could already be swelling by around $95 billion a year) which is accompanied by an aggressive policy of finance, acquisition, and soft power sweeteners all along the terrestrial and maritime Silk Roads, as well as among China’s main suppliers of essential raw materials.

Were that to be the case, it might well be that consumer goods prices come under further, benign downward pressure in the West – largely, though not exclusively, in areas where we have long since ceded the field of their manufacture to China and hence at only small immediate cost – while the recipients of China’s redistributed bounty see a corresponding upward impetus on their prices.

At least, this is what Messrs. Li and Xi will be trying to convince themselves will happen, for the truth is that even the lowest of the now-bruited GDP targets may be far beyond the scope of the country to deliver, were it ever to be honestly reckoned and openly reported.

As evidence for this contention, note that the renowned China bear, Anne Stevenson-Yang of J Capital, told Barron’s last week that the revenues of 400 consumer-oriented businesses listed on either Shanghai or Shenzhen ended a poor QIII off 4% from the year-ago period. Next, think upon the fact that November’s results for rolling 3-month electricity consumption – despite a little last-minute, cold-weather boost – were only up 2.4% on 2013. Steel production likewise was only 2.3% ahead (the smallest advance since early 2009) while cement was actually off 0.7% (the only drop seen since LEH days) and flat glass fell 4.5%. Rail freight ton-miles dropped 5.6% in the three months to October, and commercial vehicle sales plunged 9.2% last month, completing a picture of an economy where the top end, higher goods sector has undergone a classic, Austrian, malinvestment boom, followed by an equally typical and decidedly painful credit bust.

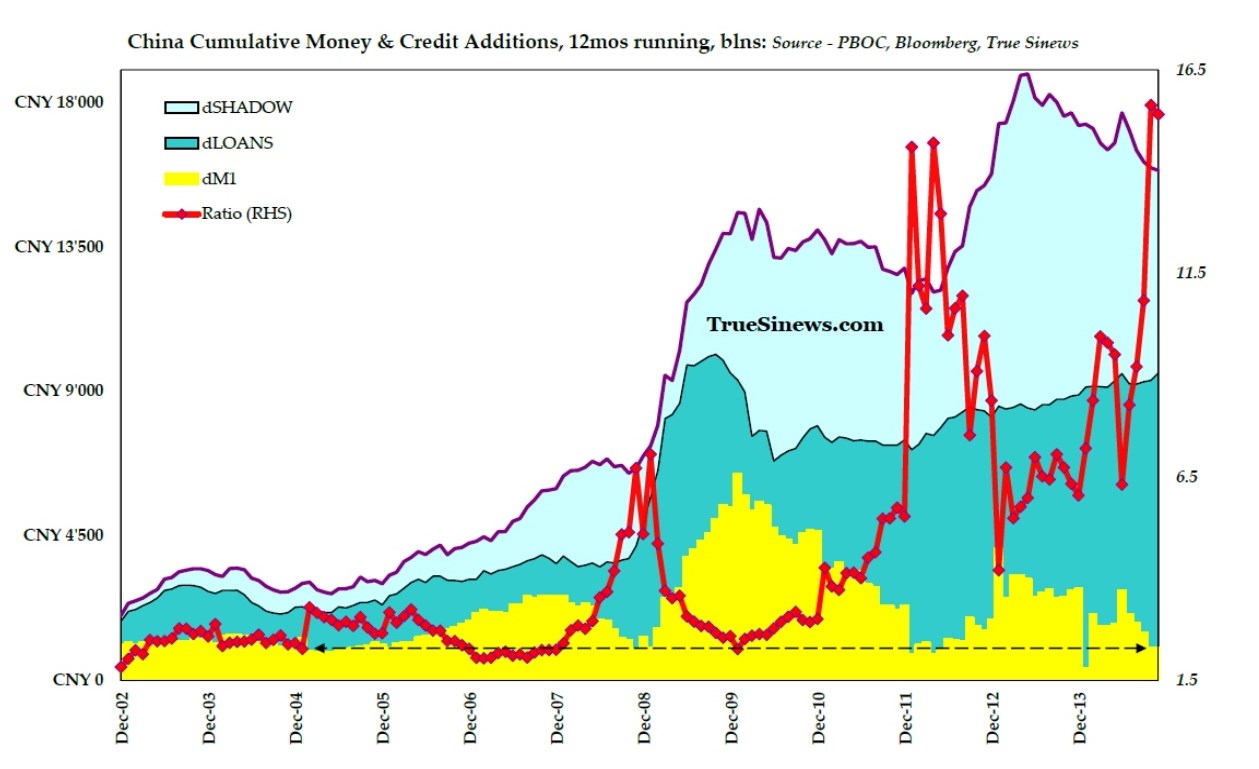

The latest money and credit numbers give ample confirmation of the malaise. The 12-month cumulative addition to Total Social Finance (TSF) – still a hefty CNY15.8 trillion – was off 10.2% yoy, but this blunt aggregate hid the difference among its component parts. Thus the tally of new bank loans actually rose 8% yoy, while entrusted loans fell 5.4% and all other forms of ‘shadow’ finance swooned at a vapour-inducing 37.4% pace.

Notwithstanding this, so weak was the increment to the money supply proper that the ratio between dM1 and dLoans hit a new (ex-January) high of 9.3:1 and that between dM1 and dTSF soared to what is at least an 11-year peak of 15.5:1. Since money proper is the only sure fire means of achieving final settlement in any transaction – as this blog title argues, after the great Richard Cantillon, ‘silver alone is the true sinews of circulation’ – this smacks of a gross lack of liquidity plaguing the system.

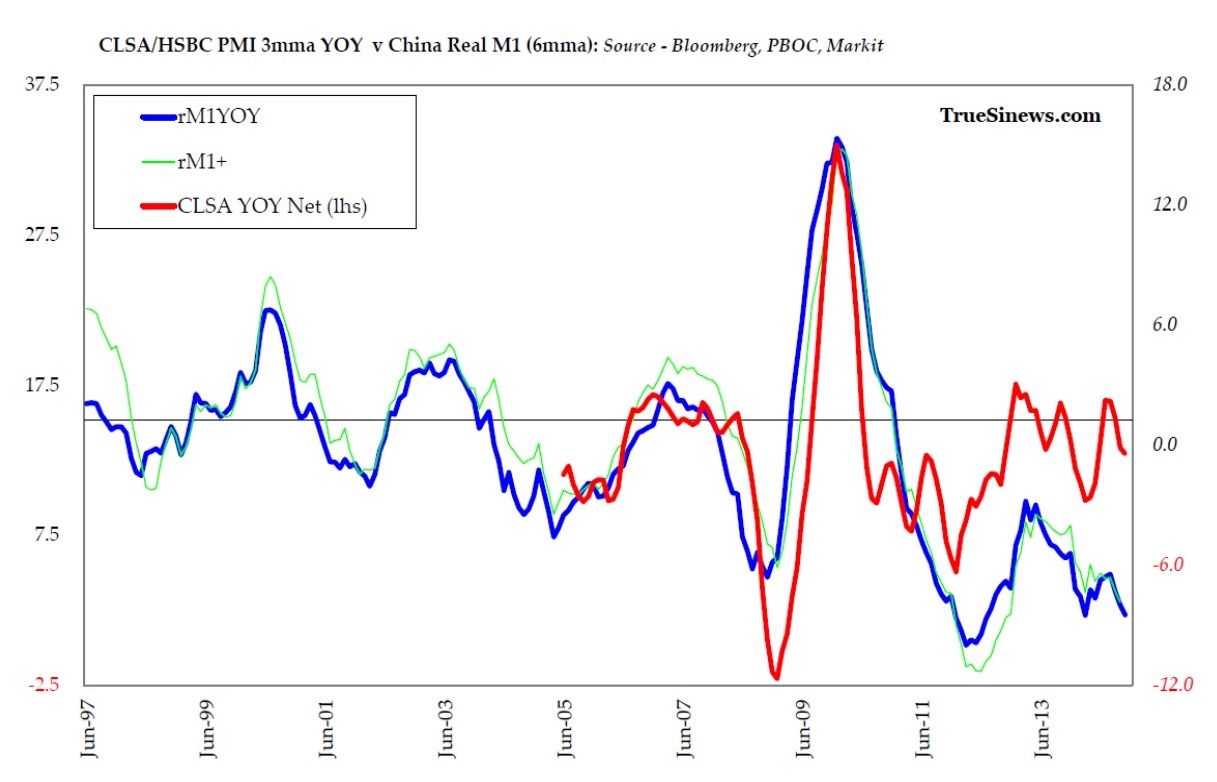

We can show for more mature economies such as Germany that the greater the proportion of money in relation to credit, the higher the revenues and the greater those expressions of business sentiment we derive from PMI-type surveys. There is, of course, nothing better than a good, vigorous cash flow – and here we mean real, foldable, dead-president cash, not the ship-and-pray intangibles of the accounts receivable line item – to lift entrepreneurial spirits and, by raising hopes that larger revenues will in some measure translate into bigger profits, to conduce to accelerated ordering, greater capex, and expanded payrolls: in short, to growth.

China has precious little of that at present, whatever the official data may pretend to the contrary and no matter how avid the appetite for stocks has become these past few, frenzied weeks.

This last, by the way, is very much a phenomenon, a hunger, being deliberately inculcated by a regime anxious to parlay unpayable debt into irredeemable equity even at the cost of inflicting severe harm upon household balance sheets and of transmuting, via expansive margin lending, corporate and LGFV risk into a less impersonal, but no less evident, kind of danger. Dear old ‘Auntie’ may think she is onto a winner as stocks rise sharply, but she may only be making an unwitting contribution to the shoring up of an edifice otherwise doomed to crumble. In doing so she therefore risks adding losses in shares to those already being suffered in gold and property, if ever the tide should turn again.

NB The foregoing is for educative and entertainment purposes only. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting investment advice. All rights reserved. ©True Sinews