While politicians anxiously check the shifting weather-vanes of public opinion and scientists squabble over facts as well as interpretations, central banks are resolutely doing what they do best – wildly exceeding their briefs and trying to drown all problems in a flood of newly-created money. As ever, the underconsumptionists worry that a lack of demand will usher in deflation, in spite of all such efforts. Some of us, however, worry more about what it will do to supply. Here, we explain why [For those who would like a podcast version please follow this LINK]:-

A Curtain Has Descended

With each passing day, it becomes more apparent just what will be the appalling consequences of the governmental rush to deprive hundreds of millions of people of their liberties and livelihoods, deny them routine medical care, disrupt their children’s education, and drive their hard-won businesses into ruin – all the while failing egregiously in the state’s proclaimed duty of protecting the most vulnerable from this nasty, somewhat selective, but otherwise not particularly remarkable, highly nosocomial disease.

With each passing day, the spin-doctors and snake-oil salesmen; the shaman and the ‘scientists’ bamboozle us with conflicting projections of the progress of the virus; offer us bluntly anecdotal tales of rare, if horrific, complications; describe wildly varying prognoses and pathologies; and bandy about more stories of treatments – whether prospective or pre-existing – some timed for maximum political effect and others to serve for a quick pump-and-dump of some dubious biotech stock or other.

With each passing day, more, not less, uncertainty is added to the list of possible interdictions, infringements on our freedoms, violations of our privacy, and narrowings of our range of lifestyle choices we are told the conquest of this disease demands: more, not less, uncertainty as to the likely duration of the imposition of such strictures and hence of the length of the sentence summarily pronounced upon us by the Star Chambers of Epidemiology.

With each passing day, too, we hear of yet more panicky measures aimed at propping up the crumbling masonry of economic life – or, if one takes a less charitable view of what is being enacted, of nationalising or co-opting much of what used to pass for free enterprise in a bleak system of Green-tinged, Track-n-Trace Corporativismo under whose operation there truly will be “Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state“.

The borders to Wuhan have not been opened: they have merely been enlarged to encompass much of the rest of humanity. It is not an Iron Curtain which has been dropped to contain us, but a green one, borrowed from a nearby Emergency Ward.

Blank-Cheque Bailey

In a world in which the head of arguably its most important monetary institute can at once say – supposedly to reassure his audience – that “We will never run out of money” and yet that his attempt to make good on this boast “…doesn’t have implications for inflation,” each passing day also brings to light some new enormity being committed against sound finance, established practice, and economic logic.

For instance, it would be funny, if not so painfully representative of the Swiftian lunacy at work, to note that CNBC recently published a piece carrying the triumphant headline: “The [US] government is bringing back a bond from the 1980s to help pay off a record deficit” [emphasis ours].

Then we have the House Organ of Davos – the ineffable Financial Times – running an article in which it pushed firmly on the open door of fiscal over-reach by arguing that, given that “…inflation might follow the pandemic, governments should finance their debt at today’s ultra-cheap rates with the longest possible maturities“.

Let’s just translate this piece of casuistry into plain English, shall we, the better to see how shameless is this prescription?

“While their pet central banks are sitting outside, gloved hands clenching and unclenching on the steering-wheel, and engines of the getaway vehicles running, the armed hoodlums of the state should grab as much of our cash as possible now and bundle it into their swag bags before we can react and try to prevent the theft.”

“The devastation wrought by the authorities’ pan(dem)ic-response has been caused by its toxic mix of monetary and fiscal overkill, taken together with the supply-inhibiting, capital formation-deterring tangle of shifting, pettifogging, but quasi-permanent regulations which are daily being put in place. Our overlords’ response has been to spend like the drunkest of sailors and to tell their creditors to address themselves to the power-mad professors at the local central bank who have eagerly offered to pick up the tab.”

“Never fear! If – as seems highly possible – this wild excess leads to an ugly downward spiral in the value of what may soon come to be regarded as a great surfeit of money, well, at least the political bandits and their armies of functionaries will be sitting pretty while the rest of us scrabble for a living amid the wreckage in which they have condemned us to live.”

In Britain, where the de jure introduction of negative interest rates seems set to lend a sheen of false legitimacy to their de facto intrusion into the Gilt curve, few stop to question whether what is in effect a raid on pensions and a creeping confiscation of savings has been subject to any form of democratic scrutiny. Instead, the nation’s elected representatives are content to sit supinely back while the appointed head of the Bank of England coyly muses about this latest demarche. In doing so, we suspect this latter knows only too well that the Market will put the command to his wish and so allow him later to say that he was only following its orders.

The absurdity of this is only heightened by Governor Bailey’s recent comment that one of the main challenges he and his minions face is – yes, you guessed it – “getting inflation to return back up to target”!

In the same newspaper interview he demurred rather unconvincingly to provide a direct answer when asked whether the post-COVID policy should involve ‘austerity’, but rather spoiled this display of false modesty by going on to say:

“What I would say is that I think there are choices, and I think those choices will be looked at very seriously… one of the reasons that the Bank… [is] acquiring a much larger stock of government debt than … would have been imagined [in the GFC], is that… we can help to spread over time the cost of this thing to society… providing the overall credibility of the framework remains in place…”

How much ‘credibility’ attaches to all this is rather dubious. Statistics are both necessarily partial and highly provisional at the moment, but consider that, in April alone, the government exceeded its pre-crisis borrowing target for the full fiscal year. Outlays for the month of £102.3 billion came to around 55% pro rata of the last figure for GDP (a level of output obviously subject to a significant, forthcoming reduction), while the £63.5 billion cash shortfall equated to over three-fifths of all expenditure and more than a third of national output.

For those not familiar with his work, Basle’s Professor Peter Bernholz, after much detailed study of past monetary breakdowns, formulated a rule-of-thumb that once the budget deficit exceeded 30% of GDP and left 40% of outlays uncovered by any form of revenue, a nation whose finances were in such a parlous state was well on the road to hyperinflation.

The fact that ALL of the necessary Gilt issuance needed to cover that yawning chasm of a shortfall was taken up by the Bank of England’s asset purchase scheme and was not met by mobilising, where needed, a still wealthy country’s deep pool of savings can only add to the dangers involved.

But wait: the BOE’s Chief Economist, Andy Haldane, explains why this must be so: “We can’t go back to jobs nightmare of the Eighties,” he wails with all the proxied compassion he can muster in order to drown out the catcalls from the back of the room, asking insistently, “And what part of your ‘mandate’, is that, Mate?”

As someone who also lived through the era in question – a time of often violent catharsis whose saving grace was that it set the stage for the fossilized Britain of the 1970s to recover an admirable degree of dynamism and flexibility over the succeeding 15-20 years – I’m forced to respond ironically that, given the mess which you, Andy, and your pals in Westminster are jointly making of matters right now, we should be so lucky as to return there!

The Cure of all, this Fruit Divine

But we should not concentrate our ire too exclusively on the denizens of Threadneedle Street. There are, after all, more than a few villains in the cast of the global pantomime of folly which we are being forced to attend.

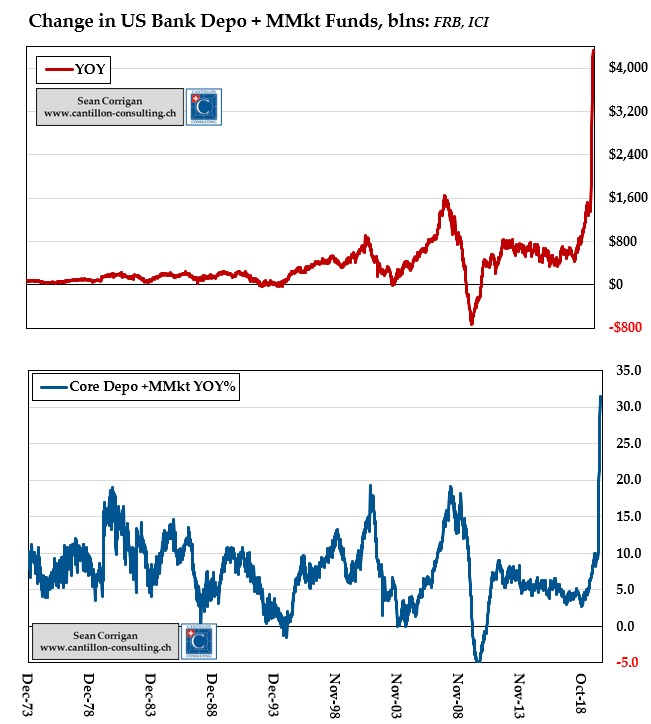

Take the US. There, a handsome $3.1 trillion in money and credit has been added in the past eleven weeks of turmoil, thanks to the tireless efforts of Chairman Powell to shake the unwholesome fruit from the boughs of the Magic Money Tree in what must be the most perilous such harvest since Eve was tempted by the Apple.

This fantastical sum works out to some $9,400 per person in a ‘dole’ which therefore amounts to $44,500 p.a. equivalent – a sum which is itself equal to the entire total of national, per capita, personal consumption, conjured up, right there, in one hit.

The poor Tooth Fairy’s wings must be fraying under the exertion of all that frantic to-ing and fro-ing!

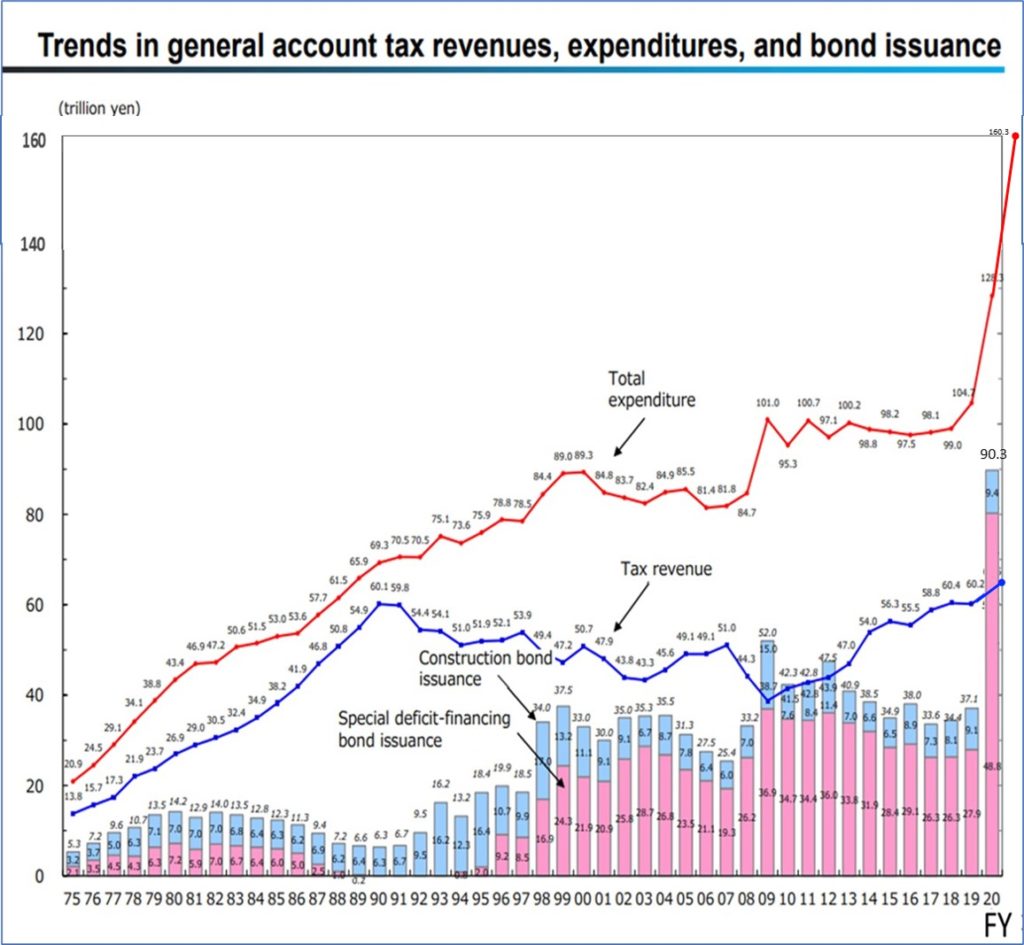

In Japan, meanwhile, the latest pledge by the central bank is to help finance Y75 trillion in new programmes over the coming months – which, at around $700 billion at current exchange rates, is also hardly chump change.

As an example of just how intoxicated everyone there has become, take the case of Professor Keiichiro Kobayashi, a member of the newly-appointed Advisory Committee to the government. Here is a man who has, for years, been one of the most insightful commentators on his nation’s post-bubble problems, as well as one of the most resolute champions of fiscal consolidation. Indeed, only in January, in his role as Research Director of the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research, he was calling on the government to “Repair the Fiscal Roof While the Sun Is Shining”.

Come the coronavirus outbreak and he has turned full-circle, leading demands – to which that same government readily acceded – to institute a Y24 trillion annual programme under which a stipend of Y100,000 a month will be paid out to those suffering a loss of income: an example of the contentious ‘Universal Basic Income’ which, its advocates say, should be maintained, if necessary, for the three to four years (!) it may take to develop a vaccine.

No wonder his Keio University colleague, Takero Doi, is instead drawing parallels with the inflations suffered after World War II when war-damaged supply was largely overwhelmed by war-inflated money. This is a scenario with which, as the reader will see, we have a great deal of sympathy.

Elsewhere, the European Union may still be haggling over just how to next drive coach-and-horses through its tangle of oft-ignored treaties and overlapping jurisdictions, but its own monetary Cardinalate hasn’t needed any further prompting, with the ECB having already swollen its assets by $890 billion in the few, short weeks since the middle of February – enough, notoriously, to provoke the condemnation of the German Constitutional Court in the process.

To make a rough and ready tally of such measures, we can calculate the increase in the narrowest (but also most frequently updated) count of so-called ‘base’ money – namely, the sum of currency issued and reserve balances – printed up by these three Big Guns, plus five others from among the world’s more influential central banks (a list which, incidentally, does not include the People’s Bank of China).

This calculation shows that they have jointly added over $3 trillion dollars in ‘high-powered’ money to the pot during these past 10-12 weeks – an annualised rate of increase from the starting point of no less than 150%!

Let us be clear, despite its highly suggestive name, this type of money is not mechanically multiplied up into higher levels of overall bank lending as the textbooks (and all too many trigger-happy commentators) might suggest. Indeed, in a world where interest rates are at or below zero, yield curves are flat, and banks are generically constrained by their capital, rather than their reserve, quotients, it may simply substitute for the regular monetary additions which are made through everyday commercial channels. Such was indeed the experience on several occasions, in the aftermath of the GFC itself.

But that does not mean such an inordinate increase comes with no malign consequences whatsoever. Indeed, in China, the fear of such perverse effects has sparked a fierce public debate over the issue of whether the law should be changed to enable the central bank to assist the government directly in issuing the CNY2 trillion in extra bonds it currently proposes to launch as part of its recession-fighting counter-measures.

To this point, the PBOC seems to have prevailed in its resistance, its argument best summarised by MPC member, Ma Jun’s, admonitions that to venture into this forbidden territory is to encourage the fiscal authorities to ‘lose all discipline’, with ultimately disastrous results for all.

It is not entirely cynical, however, to note that such disputes are partly semantic since the difference between the Bank buying paper directly from the Treasury and acquiring it from, or providing easy finance to, other intermediary purchasers, a mere day or two after it has been auctioned to them, is extremely moot.

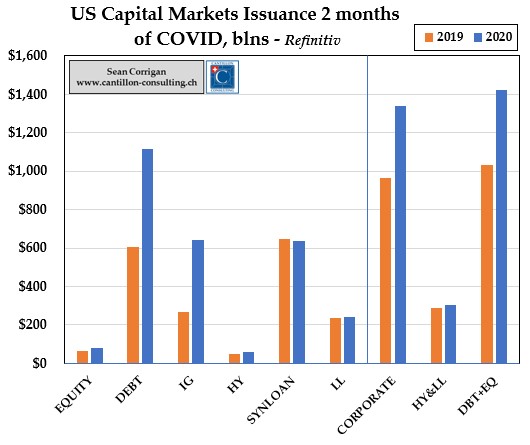

However we might view such more or less transparent machinations, what we must not lose sight of is that a balance is yet to be struck between the new monies created, the new loans granted, and the new bonds being issued (the latter are also presently setting records in the US, at least), and the credit which will inevitably be destroyed by default, write-down or equitization as the casualty list grows.

It is partly on this ground – chosen partly by appeal to a series of faulty analogies with what occurred in the wake of the Lehman collapse – that the battle lines between inflationists and deflationists are currently being drawn.

The war itself has still to be fought but, for our part, we find it hard to shake the conviction that the wider the range of activities that the state decides to bail-out, guarantee, or take outright command over – and the more determinedly it continues to flex its new-found financial freedoms to run large deficits – the less likely all this is to result in net monetary destruction, but rather in a re-routing of revenue streams and a redistribution of what wealth still remains, once the crisis passes.

As a brief aside, it is here we run into a crucial issue that the politically-convenient doctrine misleadingly known as ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ glibly overlooks. This is that the flaws inherent to its naked accounting chicanery are not just those which are concerned with inflation or the lack thereof, but rather with the empowerment of the Leviathan, warfare-welfare, surveillance state. The separation of sword and purse as a limit to that very encroachment has been a keystone of Anglophone political liberties for 400 years yet the MMT cranks would happily weld the two indivisibly together.

In this, they forget that it is not, after all, cannon which are – as the Sun King once had inscribed upon his larger specimens – ‘Ultima ratio regum’ – the ‘final argument of kings’ – but the laws of legal tender. We would do well to make sure the battery they comprise does not come to be trained directly on us.

Pieces of Eight

To return to our theme, at this stage of events, we are all a little like Ben Gunn in the classic adventure story, Treasure Island. Gunn has the pirate’s loot securely in his control but, being marooned on the island by his shipmates, he has no opportunity to spend it. Demand, here in Contamino Bay, has perforce been severely curtailed in a like manner. But nowhere – in the developed world, at least – has the volume of money and credit been similarly restricted.

To echo the Twitterati’s favourite, half-understood ‘Phrase of the Day’, monetary ‘velocity’ – the ratio between the stock of spendable claims and the spending currently being done with that stock – has thus fallen dramatically. But rather than invoke the dark shade of Keynes and mindlessly rehearse his followers’ ‘liquidity trap’ confusions, bear in mind that it is the opportunity to spend – not the means, or even the will – that is presently lacking, in the main.

It should therefore be evident that it is only when we are again granted parole and the armed guards standing between us and the shops are stood down, that the clash between monetary evaporation through bankruptcy and its heavy precipitation through the workings of the joint Treasury-Central Bank penchant for Destructive Creation will come to the push of pike. At that point we will rapidly discover that the monetary conflict will necessarily involve a real-side interplay between failure-depleted demand and greatly-impeded supply.

No doubt, there will be fire sales and falls in the prices of all manner of productive inputs when first we begin to restart the assembly lines and empty the store-rooms. Adding to this effect will be the forced retrenchment of those closed down or thrown out of work and hence left with little inclination to spend whatever money they do retain, whether as individuals or as firms.

On the other hand, supply itself is going to be impaired by the adoption of rules such as two-metre distancing, the mass provision of face masks and hand-sanitizers, the observance of strict occupancy ceilings, and the need for extra personnel variously to supply and enforce these changes, as well as to wipe the place down after every customer leaves.

Furthermore, an already nascent trend to promote ‘onshoring’ and ‘deglobalization’ can only be intensified amid the widespread clamour to cut ties to the new pariah nation, China – a country whose 21st century urbanization drive ) has been one of the prime sources of tradeable goods disinflation these past two decades. This will drastically reduce the international division of labour and so serve to strengthen the hand of insistent domestic wage bargainers even beyond the burgeoning state sector.

Reinforcing the effects of such rampant mercantilism and primitive autarky will be the fact that the State will have no appetite whatsoever to resist the demands of its armies of ’key workers’ and ‘front-line heroes’ so fresh from their apotheosis in the faux ‘War on COVID’.

Even were there to be reluctance to accede to such industrial blackmail, the bad ‘science’ next to be followed will consist of mainstream economics Wormtongues whispering their welcome exhortations into willing political ears that any semblance of ‘austerity’ is to be eschewed if the government is to make up as rapidly as possible for the economic folly of its own lockdowns.

Compounding the manifold regulatory frictions will be the ever-present fear of legal tort should either a worker or a customer happen to sicken on one’s premises. On top of this, there will inevitably be a further layer of Eco-Soviet Five Year Planning woven into the various relief packages; a drive which will paradoxically be aimed at proving outlets for ‘investment’ and relief for unemployment while also deliberately perpetuating some of the penury of Lockdown by restricting full access to the bounties of modern industrial society. Economic vitality will be further sapped by the spreading technocratic arbitrariness of ‘Green Finance’ initiatives and the ‘New (Ab)Normal’ social-engineering transport programmes.

Each of these of these factors is one which can only augment the costs facing every provider of goods and services – and simultaneously in one tending to reduce the producers’ scope for offsetting these costs by means of increases in productivity. As this progressively threatens to price individuals out of work and to force businesses to the wall – much as the mix of militant labour and dirigiste politics did, back in the 1970s – concerted attempts will be made to inflate them all back into employment, again just as they were throughout most of that previous, miserable decade.

If we are right in our reasoning here, what this means is that though job rosters may not easily reverse their shrinkage, nor all businesses, alas, be fit to be re-opened, prices will nevertheless begin to rise – and, rest assured, a clear majority of our titular Monetary Guardians will lustily cheer them on their way, when and if they do.

Hard times lie ahead.