The poster girl of the voguish crankdom that is Modern Monetary Theory (“MMT”) – Stephanie Kelton, has been out pimping her new book – “The Deficit Myth” – with a great deal of help from the unofficial PR department which she seems to have, nestled within the House Organ of Davos, the execrable FT.

Here, Professor Kelton – for all the puffery about how fearless and radical is her approach – is pushing at an open door: a gaping aperture in the last bastion of economic rationality that is being held open by no less than Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, a man who recently went on record to boast: “We will never run out of money.”

We shall return to Chairman Powell later, but, for now, let us take a brief look at Madame MMT’s magnum opus in order to get a sense of her penetrating wisdom and intellectual profundity.

Loosely condensed, her genius idea starts with truism that for every borrower there must be a lender. Move over, Polonius! From that trite, if uncontroversial launch ramp, she then proceeds to jump a veritable canyon of non sequiturs to argue that this removes all constraints on state spending.

To paraphrase our economic Evel Knievel: “That means that the government’s -$10 is always matched by +$10 in some other part of the economy. Balance sheets must balance, after all. The government’s deficit is always mirrored by an equivalent surplus in another part of the economy,” And this is about the sum of what here passes for wisdom.

Now, anyone who tries to argue about how a complex, dynamic system works by taking intermittent snapshots – i.e., by compiling periodic, tautological accounting balances and stopping there – is a simpleton or a charlatan or both. That is a process akin to flash freezing a living cell and arguing that a simple chemical analysis of its constituents will tell you all you need to know about the subtleties inherent to its metabolism, not to say its future evolution.

While one may entertain genuine doubts about which of these two categories – fool or faker – Madame MMT falls into, there seem to be no others into which she and her crew can rightly be put.

We have expounded at length upon the second-hand idiocies of MMT [the interested reader will find one such discourse at this LINK], so here we will limit ourselves to the one principal objection we must make to her logical chicanery.

MONEY FOR NOTHING = NOTHING FOR MONEY

Suppose the State issues a T-bill to a bank which accordingly credits its account with $100. This sum is then made over to some designated recipient – whether someone enjoying the overt welfare afforded to the hard-up or the hidden one of being a functionary on the public payroll.

That recipient now comes to me clutching his cheque book and asks to buy something I happen to have up for sale. Not knowing how he – or the State before him – came by this money, I naturally agree to give him the relevant quantum of my scarce, real goods in exchange for it and – for the present – think little more about it.

Now, yes, if we press the pause button right there, I am shown to have a $100 claim on the bank while it still has the original T-bill as its corresponding asset, leaving only the state with an unmatched obligation to meet – so, cancelling out the bank’s offsetting positions: government debt (minus) = my asset (plus). QED. MMT Rules!

Ay, but here’s the rub: once those real goods formerly in my possession are consumed, unless they have been put to some (re)productive use, my $100 claim is an empty one. There is nothing now, either currently in existence or in realistic prospect, which I – or any other poor unfortunate whose goods I subsequently manage to acquire in exchange for that money – can hope to buy to replace them.

Now imagine doing all this not with $100, but $100 thousand. Or $100 million, or $100 billion. Or even – the way things are already shaping, here in Camp Corona, long before Stephanie Kelton’s disciples get their hands on the levers of power, $100 hundred billion.

As you can see, instead of our money performing its unquestionably beneficial role as a reliable medium of exchange, we have been gulled into playing pass-the-empty-parcel or – as Kelton’s beloved Keynes once snidely remarked – into passing ‘the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the other fellow.’

As transparent as it is, Ms Kelton’s entire, book-length presumption is that we can all be persuaded that it is somehow possible to build an earthly Paradise on the basis of that one, cheap trick.

We could next expatiate on the perils of putting so much power over resources into the hands of the agency least likely to use them fairly, profitably, and responsibly – viz. the state – and we could also remark that Ms Kelton was long preceded in her ‘Modern’ imaginings by one Beardsley Ruml, erstwhile NY Fed chairman, as far back as in 1945.

But for now, let us leave you with a brief summation, as follows:-

MMT is an annoyingly recurrent fad which should be dismissed out of hand as being nothing more than a dangerous piece of sophistry which tells the most profligate imaginable group of spenders of Other People’s Money that not only is there no practical limit to their incontinence, but that they should consider their every indulgence in it to be of highest possible service to the public good.

MICAWBERNOMICS

Adding to that temptation, a different, but highly complementary canard currently doing the rounds takes the rough form of the contention that: “While yields are low, the public debt is no burden – and if yields were ever NOT to remain low, that burden would rapidly become too much to bear – ergo, yields will always BE low”

This is to elevate the mantra of Dicken’s Mr Micawber to the level of policy prescription:

“Annual income twenty pounds; annual expenditure nineteen [pounds], nineteen [shillings] and six [pence] – result happiness, ! he would declaim. “Annual income twenty pounds; annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six – result misery.” “Therefore, annual expenditure will be permanently fixed at £19 19s 6d,” comes the wishful rejoinder from today’s pundits.

Clearly no-one espousing this view understands the difference between real resource costs and virtual, financial ones so let us step back a pace or two to see why this superficially reassuring argument is both misplaced and mischievous.

It can hardly be contested that State’s (mis)handling of the coronavirus crisis has destroyed or impaired tremendous amounts of productive capital – a loss which it is imperative neither to understate nor camouflage.

With this in mind, the regrettable fact that the gazillion new IOUs which it has issued as a partial (and presumably a temporary) recompense for this loss will come with artificially low interest rates is absolutely NO cause for cheer: in fact, quite the converse.

The continual attempts to hide, smear out, and insidiously re-allocate the bad consequences of past economic and political follies are what keep adding to the increasing magnification of the shocks which are felt every time we hit a speed bump. Since the present degree of such studied obfuscation seems set to dwarf all previous ones it is hard to resist the inference that it risks giving rise to a series of malign repercussions on an equally extended scale of severity.

Such misplaced efforts at hiding and redistributing the pain of loss are not only counter-productive in a narrow, economic sense but they rank highly among the very things which increase perceptions of a growing inequality of treatment as well as of outcome and so corrode the body politic.

“Argh! Populism!” cries a now-threatened elite wholly responsible for this lamentable degeneration but yet seemingly either unaware of, or indifferent to, the fact that its policies are the ones spreading the reach of the inherently corrupt, Corporatist State while also enriching leveraged financial speculators at the expense of the Forgotten Men and Women who are contrastingly both prudent and hard-working in the main.

Therefore, do not let yourself be fooled: we will not escape paying for our leaders’ sins, no matter how low the level at which they succeed in nailing bond yields in the meantime.

NEGATIVE VIBES

One of the most vocal advocates of cultivating, rather than extirpating this knotweed of monetary confusion is a certain Kenneth Rogoff – a bright star in a firmament studded with countless, twinkling examples of similar ‘experts’, each happy to radiate their own brand of Swiftian lunacy in our direction.

Friend Rogoff’s distinction from his fellow inhabitants of Laputa is that he thinks we can best try to refloat the economy by driving recalcitrant savers and importunate creditors to the wall in place of the long bull market’s dense detritus of deadbeat debtors.

He wants to do this, of course, by slashing central bank-imposed rates far below zero and abolishing cash as a medium of exchange to prevent us from avoiding the costs of his ruse.

Under his panacea of Super-NIRP, then, we’d be paying people – and paying them handsomely at that – to borrow. Hmmm. I wonder how much new debt that will tempt them to take on as a cure for their existing disease of overborrowing?

The good professor, however, sees no such problems with his scheme. As he explains:-

“For starters, just like cuts in the good old days of positive interest rates, negative rates would lift many firms, states, and cities from default. If done correctly [his word, not ours]– and recent empirical evidence increasingly supports this [Really? Where, exactly?]– negative rates would operate similarly to normal monetary policy, boosting aggregate demand and raising employment. So, before carrying out debt-restructuring surgery on everything, wouldn’t it better to try a dose of normal monetary stimulus? “

For those of you who don’t understand the sheer madness of this proposal, imagine you’re shipwrecked on a desert island with your only source of provision to be found in the few boxes of canned foods you’ve managed to salvage.

Rogoff thinks your chances of survival will be enhanced if you pierce all the containers, now, and then try to guzzle the contents of as many as you can before they all go off. On this reasoning, Tom Hanks’ character in Castaway should clearly have thrown all those Fedex packages straight back into the surf which first washed them up. That version of the movie would never have lasted past the first reel.

Rather than have one bad firm fail – or force one worker, not having his labour used productively as it stands, to seek other, more profitable employment – these fools would force those who DO thrive -and the savers who enable that success – to subsidise economic losers, or else be forced to watch their seedcorn burn.

This monetary scorched earth policy is the economic equivalent of our debilitating coronavirus ‘lockdown’: we are told we should ruin the well-being of the healthy and vigorous mass to spare ourselves – temporarily, in most cases – the sad demise of the unfortunate, susceptible few.

Running out of RopeTo finish, let us turn to the agency which is at the forefront of making a de facto reality of Ms Kelton’s febrile imaginings – and one which is being urged to compound that crime by implementing Rogoff’s even more perverse proposals: step forward, the Federal Reserve.

Having endured months of opprobrium for daring to trim his institution’s corrosive overreach last year, during the brief interlude wrongly described as ‘Quantitative Tightening’, Chairman Powell has now dropped his former reticence with alacrity; donned his firefighter’s clothing; dropped down the sliding pole; and rushed, with sirens blaring, to douse the flames of recession.

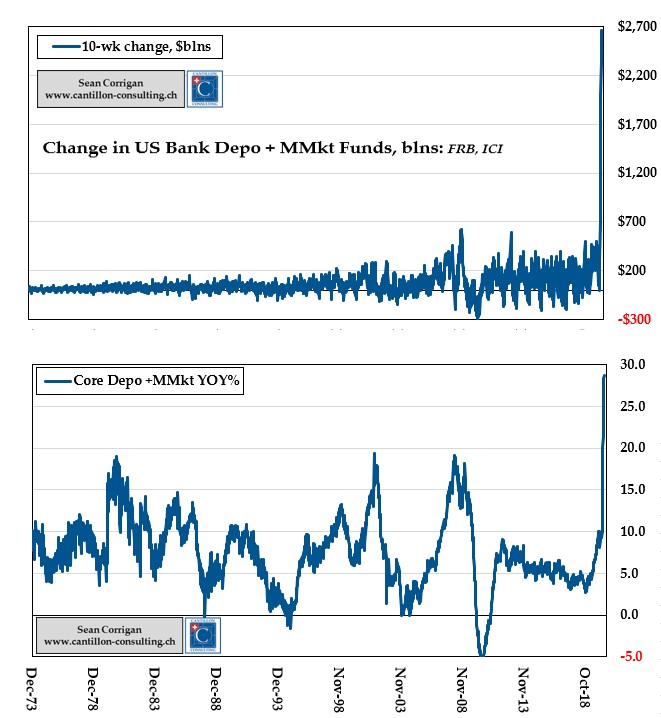

Alas, it may soon be revealed that he has connected the hose to a fuel pipe, rather than a water main, having given rise to the creation of a $2.5 trillion increment of money and its nearer substitutes in a bare 10-week burst of scatter-gun inflationism: a vast sum equal to the one which took all the previous 43 months of expansion to last be called into being.

Clearly, Mr. Powell, there is nothing, as you say, to suggest you will ‘run out of money’ any time soon.

What you may, however, ‘run out of’ is our willingness to accept that money in exchange for our goods and services. To see why that might be, we suggest that you refer to the arguments advanced above against Stephanie Kelton’s Free Lunch, Tooth Fairy economics.

Enough of this madness, please!